Discover Our Founding Fathers’ Favorite Flowers

By Linda Lee

In honor of July 4th, and Presidents Day, we thought of looking at the Founding Fathers and how they spent time in their gardens.

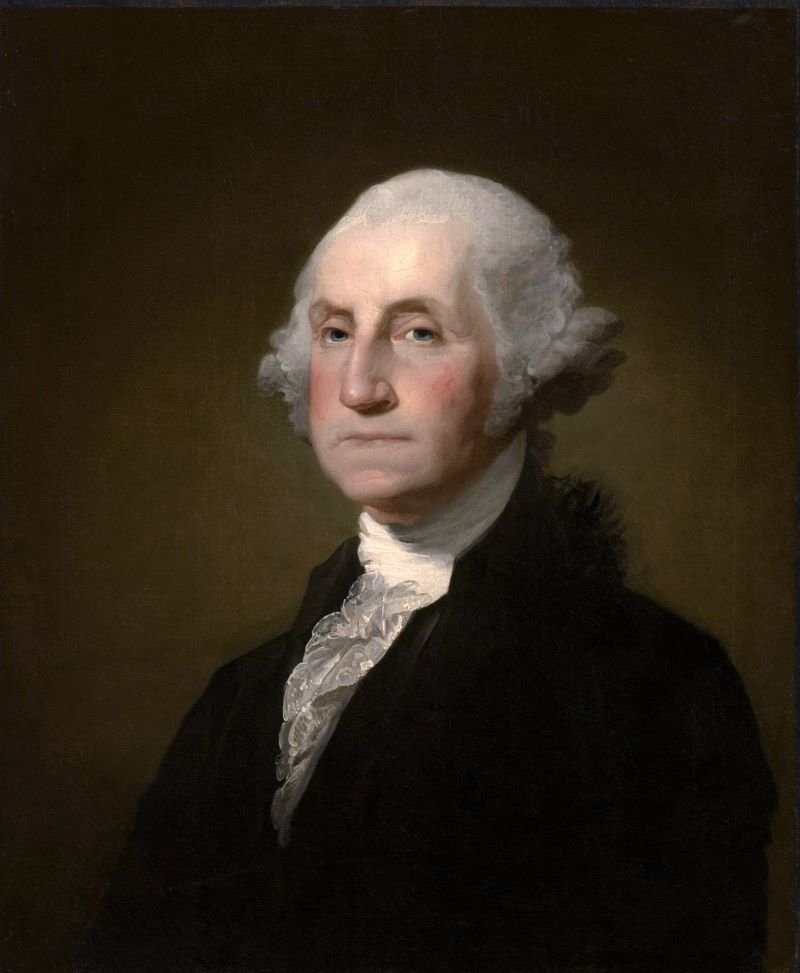

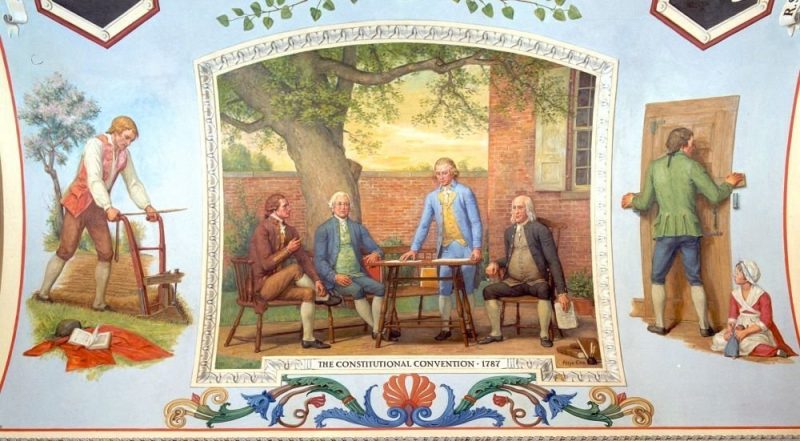

Thomas Jefferson, George Washington and Alexander Hamilton were farmers, as were most men of their time – even if they became soldiers, lawyers and statesmen. Benjamin Franklin, seated at center in the above painting of the Second Continental Congress, was a scientist with a deep interest in seeds as a source of American self-sufficiency. John Jay, who was president of the Congress and navigated many essential treaties, retired to life as a gentleman farmer in Westchester.

They were knowledgeable about plants, including flowers, and four of them knew the Philadelphia botanist John Bartram and ordered plants from him. Outside of their occupation of the White House and higher reaches of public service, each of them had farms or estates with flower gardens. In Franklin’s case, it was the garden behind his townhouse in Philadelphia, perhaps best known for his mulberry tree, under which details of the Constitution were hashed out.

To maintain their legacies, their flower gardens, except for Franklin’s, are maintained today to honor the men who shaped the United States of America. As Thomas Jefferson once noted, “Too old to plant trees for my own gratification, I shall do it for my posterity.”

George Washington’s Pleasure Garden at Mount Vernon

Washington’s greatest interest may have been manure; he once had his workers and slaves set up ten experimental boxes with different kinds of manure, and declared horse manure the best, and chicken manure the “hottest.” We do know that, as the owner of Mount Vernon and other plantations, he was expected to have a pleasure garden, and that he liked yellow flowers: African marigolds, seeds for which were being sold in the Colonies as early as 1730, Brown-eyed Susans and “Basket of Gold” (Aurinia saxatilis), below, a ten-inch tall perennial that lined garden paths.

The list of flower seeds available at Mount Vernon is an attempt to duplicate what might have grown there at the time: globe amaranth, pincushion flower, Sweet William, lavender, cone flower, mallow and other old-fashioned flowers. Because he ordered trees and plants from John Bartram in Philadelphia, it is likely he ordered from Bartram’s amazing nursery list in 1792, preserved in government archives.

It included a rhododendron with large rose-colored flowers, three types of viburnum, Mock orange “a sweet-flowering shrub,” a kind of wisteria he said was “a rambling florobundant climber,” hydrangea and what Bartram called hibiscus, and is now called scarlet rose mallow. (We know Thomas Jefferson ordered it for his garden; even in 1792 Founding Fathers were not immune to a nursery description like “a most elegant flowering plant; flowers large, of a splendid crimson colour.”)

Washington lived only two years after stepping down as President, but his career as a successful general and important land owner before he became president marked him as a person who merited visits from dignitaries, although he far preferred sitting at home with Martha and reading.

One visitor to Washington’s home remarked on a visit to his pleasure garden that it had a “great variety of plants and flowers, wonderful in appearance, exquisite in their perfume and delightful to the eye…” In fact, his pleasure garden was kept narrow in deference to vegetable, fruit and croplands. But the flowers were paid attention to and Washington did indulge in a rich man’s greenhouse, where he could grow rare and exotic plants and flowers, grapes and orange, lemon and lime trees. Putting orange blossoms on a dinner table certainly would have been a coup.

For years the groundskeepers at the Mount Vernon National Park laid out the Upper Garden as a formal garden with boxwood and a rose garden as if Washington might have been a French king. It was only in 2010 that deep horticultural research revealed that no such boxwood existed in that place at Mount Vernon.

Instead, Washington planted his flowers around the outside of his Upper Garden vegetable gardens, the garden closest to the house. In other words, his pleasure gardens were along the pathways surrounding his working kitchen gardens, which is what the upper gardens now look like at Mount Vernon.

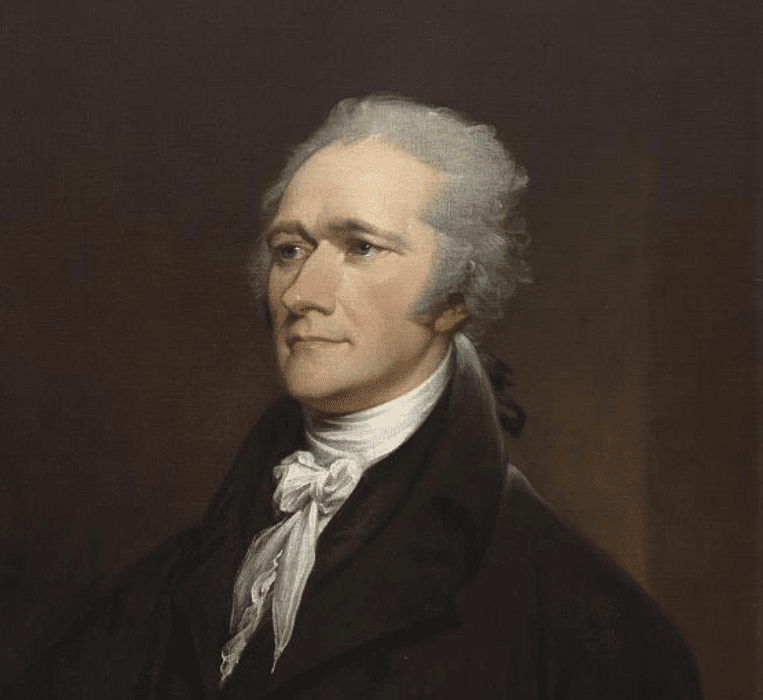

Alexander Hamilton, Everyone’s Favorite Founding Father

Alexander Hamilton began construction of a house on 32 acres in Upper Manhattan, in what is now Harlem, in 1802. He called it the Grange, in honor of the ancestral Hamilton family home in Scotland. While the Grange was being built, he and his wife and their seven children lived in a townhouse in lower Manhattan. This is after he stepped down as Inspector General of the United States Army in 1800 and quit a long and storied life in Washington, where the White House had just been completed.

Hamilton had spent most of his life deep in books and government, and considered himself a poor farmer. He set out to change that by close association with David Hosack (his personal John Bartram). Hosack was the family physician, who was with Hamilton when he died in Greenwich Village after his duel in 1804.

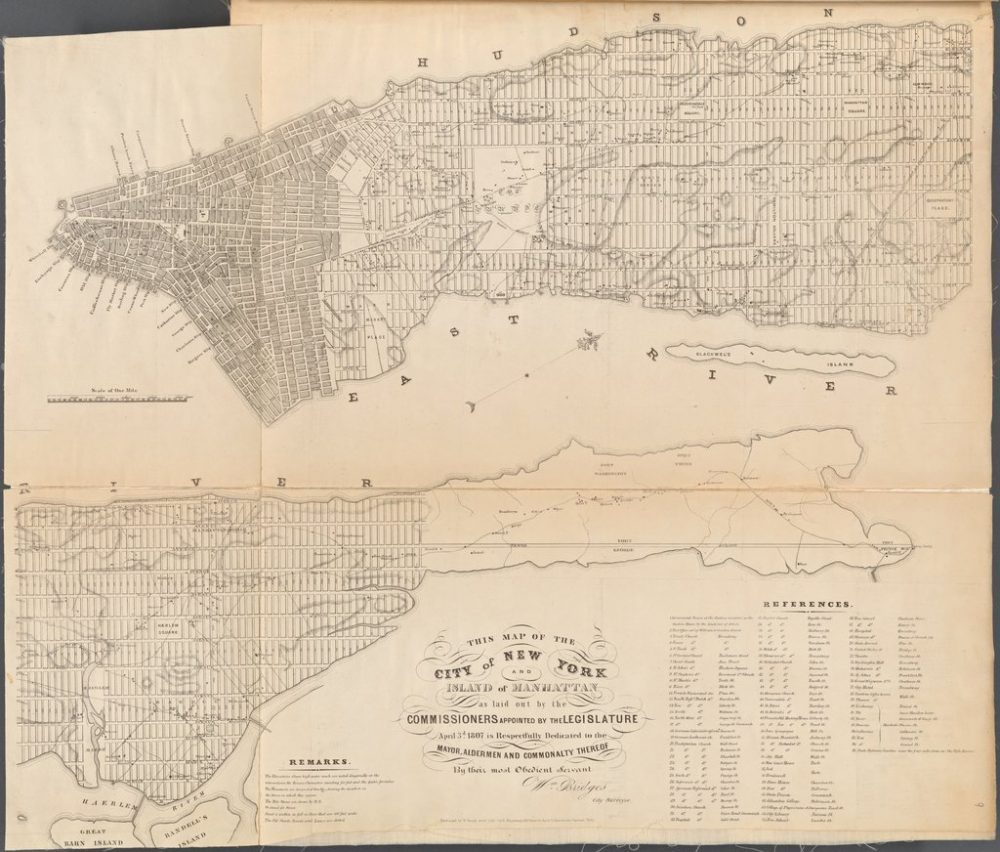

Hosack was also a generous friend and teacher, a professor of natural history at Columbia College, which was located in the Trinity Churchyard downtown, 600 feet from Bowling Green. At the time of the Revolution and in the early years of the Republic, New York City had a population of 60,000, and the northern boundary of the city was the Collect Pond, several blocks south of what would become its drainage ditch and then Canal Street. Even in 1808, when the legislature hired a planner to imagine streets all the way up the spine of Manhattan, the shoreline was better known than the interior, with its swamps, ponds and springs.

It was Hosack who gave Hamilton cuttings and bulbs, and who tutored him in botany. When Hamilton rode from lower Manhattan to 141st Street, to visit the Grange estate and construction site, about eight miles away along a dusty trail called Bloomingdale Road, it was convenient to stop at Hosack’s botanical garden, which stretched from what is now 47th Street to 50th Street from Fifth Avenue to Sixth Avenue. Hosack called it Elgin Botanical Garden, in honor of his own Scottish ancestry. The site is now the location of Rockefeller Center.

Hamilton, a fast study, wrote instructions in 1803 for the siting of flower beds at the Grange. “If it can be done in time I should be glad if space could be prepared in the center of the flower garden for planting a few tulips, lilies and hyacinths. The space should be a circle of which the diameter is Eighteen feet: and there should be nine of each sort of flowers; but the gardener will do well to consult as to the season. They may be arranged thus.”

Here he drew a circle and even made a careful diagram. The blank after hyacinths remained blank. He forgot the name of a flower, perhaps daffodil, and was to consult with Hosack. He continued: “Wild roses around the outside of the flower garden with laurel at foot.” He noted, by the way, that any of the work he listed, which started with fruit trees, “must not interfere with the hotbed.”

Because he mentions a “flower garden” twice, there must already have been flowers growing there, perhaps from a previous owner. He was now adding a feature of spring bulbs. He lived long enough to see them flower.

As for the hotbed. It both tells us when this was written, in early spring 1803, and reminds us what Hamilton had learned. A hotbed is a relative of a cold frame. It uses fresh manure, straw, wood chips, tree branches and leaves inside a wooden frame that rises several feet above the ground to create a heat-generating pile where peppers and tomatoes will happily grow, or where the gardeners can start seeds early in the year for transplanting.

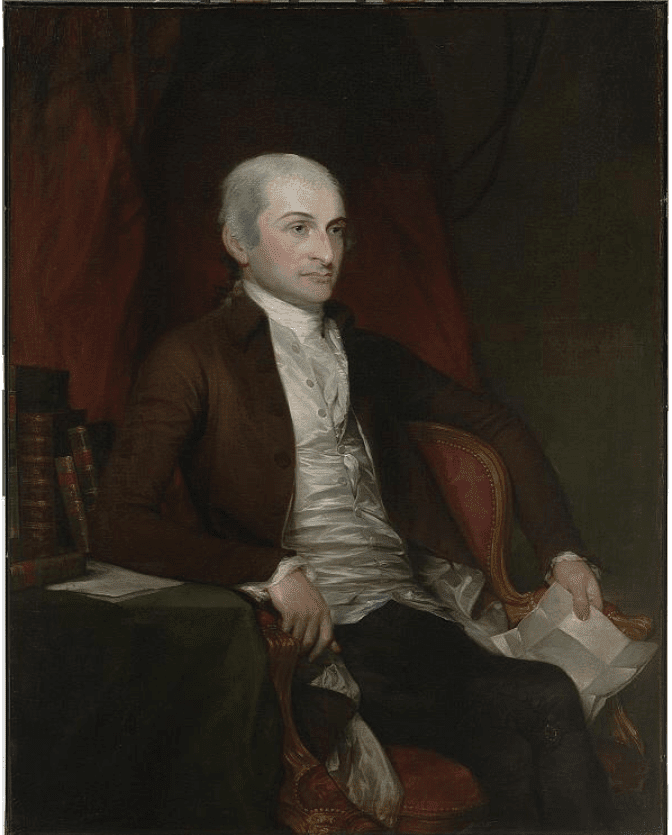

John Jay, the Sometimes Forgotten Founding Father

John Jay was not at the First Congressional Congress, nor did he write the Declaration of Independence. But Alexander Hamilton conferred with him in writing the Federalist Papers. As President of the Second Continental Congress, he oversaw appointing George Washington as General of the Army, then served as Secretary of State during the Revolution.

He was never President, but Washington gave him first choice of any cabinet seat, and Jay chose the Supreme Court. He helped write the New York State Constitution. And when he was elected Governor of New York, he stepped down from his seat on the Supreme Court. Four years later, in 1799, he outlawed slavery in New York, a year after he himself freed his slaves.

In 1801 he and his wife, Sarah, retired to their farm in Bedford, Westchester County. As much as they looked forward to life their 1787 farmhouse, and quiet years together, Sarah died within a year, at age 45. He lived on for another 30 years as a gentleman farmer.

The 62 acre John Jay Homestead has four gardens that represent what was there during the Jay family years. The North Courtyard Garden was made blue and white to be consistent with a book of pressed flowers owned by his daughter, Maria Jay. The flowers – including violets, poppies, and irises – bloom from spring to fall. This, and all four gardens at the homestead, are tended by local garden clubs.

Benjamin Franklin, Citizen Scientist and Bon Vivant

Benjamin Franklin was not a farmer; he was a printer, columnist and scientist. He lived in Philadelphia, but just as often until late in life in London and Paris. While abroad he sent seeds back to his long-suffering wife, Deborah, but most were for vegetables he had discovered and wanted to be introduced to America, including rhubarb, soybeans and kale, which he called Scottish cabbage.

He was an intermittent vegetarian and believed in the strategic power of increasing the diversity of plants in the United States. He foresaw new conflicts with Europe, and the cutting off of shipping and trade. Thus he was eager to send seeds home.

In the 1950’s, when Allyn Cox painted a mural in the Capitol building of Franklin’s garden behind his house in Philadelphia, he pictured the famous mulberry tree, but not any flowers.

Plants were named in Franklin’s honor, and as a ladies’s man we can be sure he presented English and French women with plenty of bouquets of fragrant violets. He was wise in the ways of flirtation, even into his 80s.

But because he was close friends with John Bartram we can be sure his garden, actually the precinct of his wife, Deborah, since Franklin was gone more than he was home, was stuffed with some of Bartram’s decorative native shrubs, including rhododendron and azalea and oakleaf hydrangeas. Bartram named the Franklinia Alatamaha, below, after his friend and, although it is a member of the tea family, this tender flowering bush might well survive in a sheltered corner of Franklin’s walled garden.

Certainly, in order to keep up with Thomas Jefferson, Franklin would have insisted that Deborah plant one of those Scarlet Mallows that Bartram listed in his nursery catalog. His house, at 322 Market Street, was torn down in 1812, 20 years after his death and no trace of his courtyard garden remains although there are “ghost” structures outlining the approximate size of his house and a print shop.

Franklin was, of course, America’s First Aphorist. He once wrote, “I have thought that wildflowers might be the alphabet of angels.”

Thomas Jefferson, The American Polymath

Jefferson, the nation’s third President, knew a great deal about many things: astronomy, diplomacy, music, science, architecture, agriculture, politics, books and botany. And that is not a complete list. The nation’s third President, after Washington and John Adams, Jefferson introduced geraniums, a plant new to America, into the newly built White House. He graded and planted the South Lawn, which had formerly led to a swamp and is now known for its ceremonial splendor and Easter egg rolls.

Jefferson was, of course, a passionate horticulturist. He had inherited Monticello, one of his three estates in Virginia, when he was 26, in 1770, and begun siting and designing the house and gardens then. Specimen shade trees, nut and fruit trees were always the first consideration, along with grading and landscaping the grounds.

Within two years he was married. But within two more years, political life drew him to Philadelphia, where he was the Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress. His ability as a writer, lawyer and thinker propelled him into public life as an author of the Declaration of Independence, Governor of Virginia, Minister to France, Secretary of State, Vice President of the United States, and President from 1801 to 1809.

Because the White House was new, and the first Presidents were but temporary residents, they set about planting trees for the future. The 18 acre grounds around the White House soon included fruit trees and species that represented the states in the Union. Of necessity, there were vegetable gardens around the White House, which had a staff to support, and visitors to entertain, even in a muddy construction zone.

Not until the sixth president, John Adams’s son John Quincy Adams, were formal flower gardens planted, between 1825 and 1829. By then Washington was becoming a more suitable setting for the nation’s capital.

In Jefferson’s time, in 1801, Washington was part swamp, and not nearly as fashionable or convenient for most politicians as Philadelphia had been. Only the North Wing of the Capitol Building had been finished, and funds were non-existent for further work. Summers in Washington were notably torrid and many, even Presidents, were eager to get out of town. The House of Representatives was meeting in a temporary building they called “the Oven.”

In 1801, legislators from New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Vermont had even further to go to reach Washington, and complained bitterly. Laws had to be passed to compel attendance during legislative sessions.

Thus, the federal government was not a full-time occupation. Most members of Congress were still landowners and needed to get back to their crops and livestock. In 1801, Congress met from December to May 1, 1802. In 1802, from December to March, 1803.

For Jefferson, Monticello was 120 miles south, perhaps two days away and up in the cool mountains. He never stopped working on improving, or monitoring the planting and planning there, which included work by slaves. We have to remember that much of the building of these great plantations and estates, even the buildings in Washington, was done by slave labor.

We know that Jefferson sent seeds back to Monticello when he traveled abroad. And when he returned to the states he ordered seeds from abroad and traded seeds and plants with friends. In fact, he sent plant specimens to Hosack for Hosack’s Elgin Botanical Garden in New York. In return, Hosack made Jefferson a member of the New York Horticultural Society along with John Adams, James Madison, John Jay and the Marquis de Lafayette.

One of Jefferson’s dearest acquisitions was in 1811, from a gardener in Paris, the Painted Lady sweet pea, a genetic sport from 1737 that produced beautiful two-toned pink-and-white flowers, and had a lovely smell. Jefferson was always one to appreciate double benefits in plants.

There are books written about Jefferson’s gardens, some of them devoted to unraveling Jefferson’s sometimes idiosyncratic names in his garden diaries. He was known to create names on his own, like Pentapetes Phoenicia.

Along with Bartram and Hosack, Jefferson had his own nurseryman and garden mentor, a man named Bernard McMahon, who was based, like Bartram, in Philadelphia.

Jefferson was a devotee of McMahon’s “The American Gardener’s Calendar,” which listed chores month by month. It was published in 1806 and appealed to Jefferson’s orderly and scientific mind. Jefferson wanted McMahon to accompany Lewis & Clark on their expedition of the new Louisiana Purchase, in 1803, which would more than double the territory of the United States, and make Louisiana a state in 1812. McMahon begged off, saying he was too frail for such a rigorous trip.

Plants, gardening and nature, it seems were a deep part of Jefferson’s inquiring soul.

He wrote to a friend, two years after he left office: “I have often thought that if heaven had given me choice of my position & calling, it should have been on a rich spot of earth, well-watered, and near a good market for the productions of the garden.”

He closed by saying, “but tho’ an old man, I am but a young gardener.” He was 68, and lived to be 83.