Six Flowers That Define the LGBTQ+ Movement in History

By Jill Brooke

Expect to see a kaleidoscope of rainbow-colored roses this week for several fantastic reasons.

The Senate passed a bill to protect gay marriage as well as interracial marriage.

“What a great day,” says florist Oscar Mora, who came to this country from Venezuela to escape persecution. “So many of my friends feel safer because of this decision.”

Mora, like many florists, has been part of New York City LGBTQ+ pride marches for decades. In fact, he recently created a fabulous headdress for actress Debi Mazar (“Younger”) and now is busy making a rainbow arrangement for friends who want to celebrate.

Mora and Mazar. Courtesy of Oscar Mora

Florist Lewis Miller says florists have always contributed their talents to pride events. “Certain industries attract creative types,” says Lewis, whose Flower Flashes have given joy around the country. “The industry is and has been largely made of gay men.”

Their skill is not a small contribution. Au contraire. Those lush floral floats at parades have been catnip to the public and opened more hearts and minds to the cause.

Pride month has its roots in the commemoration of the Stonewall riots in June of 1969 after police raided a New York City gay bar, The Stonewall Inn.

For the riot’s anniversary in 1970, demonstrators carried flowers in solidarity and marched through Greenwich Village in what historians consider the first LGBTQ+ pride march.

Eight years later, a rainbow flag created by artist Gilbert Baker made its debut at the San Francisco event to symbolize Gay Pride and became an iconic symbol.

Soon after, flowers became another way to express the movement.

Courtesy of Lewis Miller Design

Courtesy of Lewis Miller Design

Baker had wanted each color to represent a message. Red represents life, orange for healing, yellow for sunlight, green for nature, blue for harmony and purple for spirit.

When the flag was first created, there was a pink color for sexuality, which was removed for design purposes.

However, flowers often have a hot pink shade and are included in the design.

“Flowers have been a part of a coded language within the LBGTQ+ community for centuries,” says historian Sarah Prager, the author of Rainbow Revolutionaries. “There are many floral symbols besides dyed roses including green carnation, violets, lavender and pansies.”

Prager helps us explore each flower and its history in the LGBTQ+ movement.

1. Green Carnation

Writer and wit Oscar Wilde popularized wearing a green carnation as a gay symbol in 1892. He instructed his friends to wear them on their lapels to the opening of his comedy, Lady Windermere’s Fan. Subsequently, it became a coded symbol that a man was attracted to men.

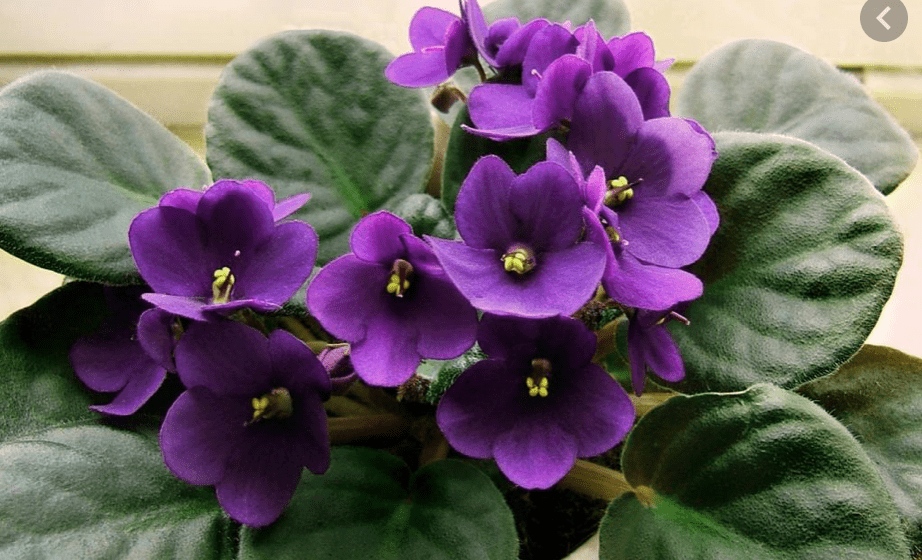

2. Violets

Turns out Sappho (c. 630-c.570), the Greek poet who lived on the island of Lesbos, often referenced violets in her ancient poems creating this association for female love. Girls frolicked adorned in garlands and had “many crowns of violets.”

“Together you set before more

and many scented wreaths

made from blossoms

around your soft throat…

…with pure, sweet oil

…you anointed me”

The coded reference to violets in the pantheon of female love endured for centuries.

In fact, a scandal occurred in 1926 when a female character in the play The Captive sent a bunch of violets to another female character. Literary scholar Sherrie Inness reported in the National Women’s Studies Association Journal that the theme of lesbianism in this play led to an uproar and calls for censorship. Subsequently, the New York City district attorney’s office shut down the production in 1927.

Violet sales also plummeted as a result of the association.

However, at the play’s showing in Paris, some women wore the flower on their lapels as a show of support.

In his play, Suddenly Last Summer, Tennessee Williams also weaved violets and its symbolism into the plot by naming a character Mrs. Violet Venable. It’s also why purple is in the rainbow flag.

3. Pansies

Marcel Proust’s Sodome et Gomorrhe referred to male-male courtship as being similar to the process of flower fertilization. Men were called “an evening botanist,” “buttercup,” or “horticultural lad.”

However, as Christopher Looby wrote in his book, Flowers of Manhood, pansy is the term that stuck—especially for those who dressed flamboyantly. The bold bright colors of the flower may have been what triggered the association.

As a result, many gay bars throughout history had names such as “The Pansy Club.”

There were periods when these bars were more accepted than others. In Harlem in 1869, the masquerade balls became popular. Later in the 1920s, drag queens like Jean Malin helped popularize gay-friendly bars in major cities, a trend that historian George Chauncey called “the Pansy Craze.”

Whereas the late 19th century restricted gay male activity to the seedy red-light district under the elevated train of the Bowery, with an even less visible lesbian life largely restricted to private salons for upper-class women, prohibition allowed the first emergence of a visible gay and lesbian life.

Prohibition forced all kinds of people to mix—all in search of the same illicit drink, and created a culture of at least mild tolerance if not outright “anything goes.” That shift raised awareness for outdated moralism of the Temperance movement.

These popular clubs were able to exist without pushback for a while. But the rise of Nazism and Hollywood homophobia, due to the Hays Commission, drove the clubs back underground. Post-war created more conservatism that resulted in the 1960s where love and tolerance were embraced once again in cities.

4. Roses

Roses are a flower sometimes referenced for the trans community. “There is a phrase, ‘Give us our roses while we are still here,” says Prager. “Trans people are murdered at alarming rates and the roses are associated with mourning since you lay roses on a grave.” Therefore, roses are a symbol to honor them when they are alive and see the beauty within. This concept was also addressed in a photography exhibit called “The Rose Project.”

5. Lavender

Lavender has been associated with both gay men and women.

“Lavender boy” was a term used for gay men in the 1920s. A guy who had any characteristic not deemed masculine enough would be accused of having “a streak of lavender.”

In fact, in 1926, historian Carl Sandburg once referred to Abraham Lincoln as having “a streak of lavender” which ran through him.

For women, lavender became associated with lesbians wanting to be included in the women’s movement.

As historian Naoko Shibusawa wrote in The Lavender Scare and Empire: Rethinking Cold War Antigay Politics, Betty Friedan labeled their involvement “the Lavender Menace.”

Lesbian feminist Rita Mae Brown and other activists fought back in 1970 by disrupting a women’s event wearing T-shirts that said “Lavender Menace.” The crowd supported them and welcomed them into the fold. Later in 1971, lesbian rights became part of the platform as a “legitimate concern of feminism.”

One writer suggested that lavender became a symbol because mixing pink—culturally connected to girls, and blue—culturally connected to boys—creates lavender. Thus, it is an important rainbow color.

Now lavender roses are often the choice of LGBTQ+ partners on Valentine’s Day for same-sex marriage.

Recently, Taylor Swift wrote a song called “Lavender Haze” which took a 50s term of being in love and modernized it. The song refers to anyone in love.

6. Tie-Dyed Roses

Although these flowers were first associated with Woodstock and the love and peace movement, it has become an iconic symbol now for the LBGQT+ community, as a result of Gilbert Baker’s rainbow flag. Its message of inclusivity and welcoming resonates with everyone in the community. The flowers, like people, are bright, colorful, varied and beautiful.

As Lewis Miller points out, “Flowers represent nature and the diversity of the world.”

Courtesy of Oscar Mora

![]()

Jill Brooke is a former CNN correspondent, Post columnist and editor-in-chief of Avenue and Travel Savvy magazine. She is an author and the editorial director of FPD.

Photo Credits: #1, PIxabay, #2, Oscar Mora, #3 and #4, Lewis Miller Design,#5 Oscar Wilde Tours, #6 FPD, #7 Pixabay, #8 Wikipedia, #9 FPD, #10 Pixabay, #11 FPD, #12 Bliss Flowers, #13 Oscar Mora