Medicine from Flowering Plants: What You Need to Know

By Linda Lee

Flowering plants and medicine: scientists are discovering new connections all the time. In some cases, they prove what ancient people already knew. Poppies have been a source of pain relief for centuries. The Egyptians chewed poppy seeds to reduce pain, and the seeds of Papaver somniferum before the poppy is ripe do contain pain relieving alkaloids. The sap can be turned into opium, or combined with alcohol to make laudanum, or turned into morphine, or codeine.

The leap forward from that was to synthesize pain killers that mimicked the action of morphine but was “less addictive,” which brought us heroin and methadone. A different kind of poppy led to the discovery of the alkaloid that can be turned into oxycodone.

Alchemist working a surgeon. Woodcut after Hieronymus Brunschwig,

Alchemist working a surgeon. Woodcut after Hieronymus Brunschwig,

(c. 1450 – c. 1512) a German surgeon, alchemist and botanist. Wellcome Library, London.

But new discoveries have found wonder drugs unknown to the ancients. The common periwinkle, or vinca, can fight cancer. The drugs derived from the periwinkle are vinblastine and vincristine, powerful chemotherapy to fight small-cell lung cancer, two kinds of leukemia and neuroblastoma. Chemists continue to look to nature, both what is underfoot and what is deep in rain forests and jungles to see what nature can provide to cure what ails us.

In 2018, the New York Times seemed astonished to report that mice fall into a state of calm and relaxation when they smell linalool, a substance in lavender. It is as powerful for mice as Valium, but without any side effects. Another study, in Arizona, found that sniffing lavender oil calmed dressage horses. So a nice soak with lavender-scented soap probably is a good stress-reducer.

But other beliefs aren’t as easy to prove. When you read claims that say something “may” or “could help” or when a description lists 30 remedies, or says native people, or the Chinese use it for… those are not scientific or proven medical claims. Even lavender hasn’t been tested on people. Who knows? Maybe linalool is a flash in the pan – effective for five minutes but no longer. Or maybe we will someday live in a linaloon-scented world, and prescriptions for drugs to combat stress will be halved.

Thousands of years ago, in both the old and new worlds, early man (and woman) tried everything (perhaps that is the real warning of Eve and the forbidden fruit). They were brave enough to try lobsters, clams, mushrooms and to sample every herb and plant on earth. Some of them died for their curiosity, or the incurious died of hunger. The rest passed along what they learned.

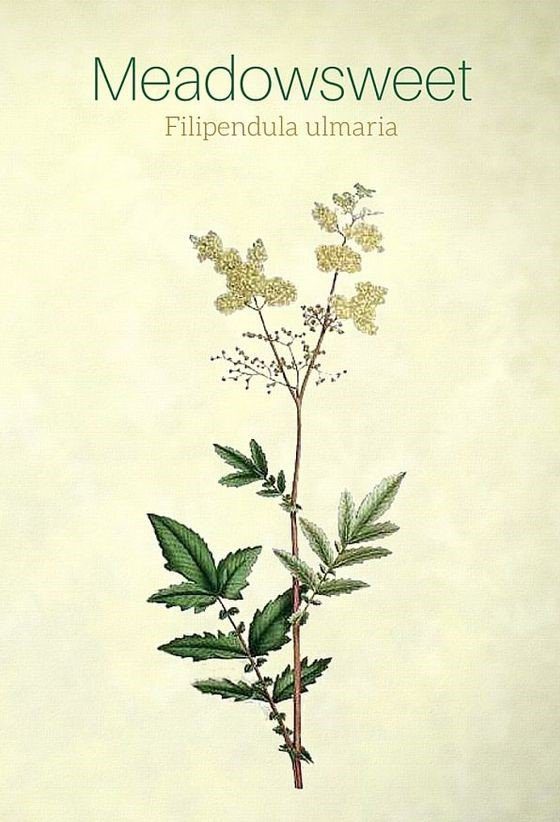

Greeks and Romans figured out that a substance in willow bark reduced swelling. Native Americans found that same something in the bark of birch and aspen trees. In 1899, German scientists discovered how to make salicylic acid powder from a lovely flowering plant called meadowsweet, the same salicylic acid in birches, aspens and willows. It was a wonder drug that could lower fevers, cure headaches, relieve swelling, help rheumatism. The scientific name for the Meadowsweet, a flower that grows in Northern Europe is spirea tomentosa, and so the company, Bayer, added an “a” to the beginning of the plant’s name and called it “aspirin.”

If you want to dig deeper on you own into scientific literature, here are some helpful tips. Scientists love to use the word “agonist.” Just remember that it’s the opposite of “antagonist.” An “agonist” helps something along.

The naturally occurring nitrogen-containing chemical compounds called “alkaloids” are essential in talking about medicinal plants. Alkaloids are especially common in certain flowering plants. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the opium poppy has about 30 different types of alkaloids in its family tree. The buttercup family, nightshade family (which include tomatoes) and amaryllis family also contain alkaloids. Derivatives from these plants often end with “ine,” as in “codeine,” “vincristine,” “nicotine,” “morphine,” “cocaine,” “mescaline,” and “scopolamine.”

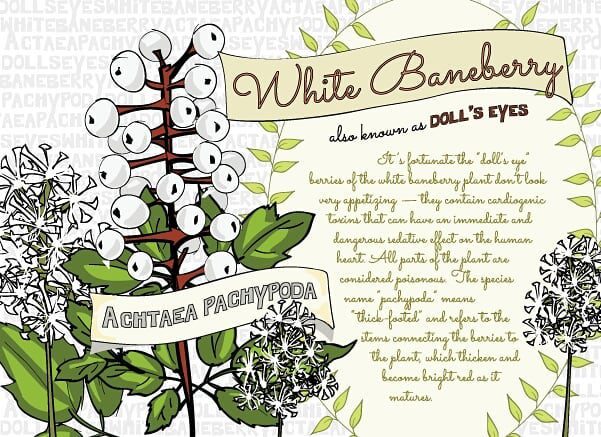

What follows will be the scientific stories behind real medicinal flowering plants, including, among many others, deadly nightshade, the foxglove, white snakeroot, angel’s trumpet, doll’s eye, oleander, monkshood, henbane, feverfew and flowering tobacco.

Here are just a few examples. In entries that will follow this introduction, you will find full descriptions of the many scientific and medicinal uses for flowering plants. We will try throughout to separate fact from what is dished out in beauty magazines about the wonders of cucumber scrubs, and sea salt. We are talking science.

It does not always jibe with one’s hopes, especially when a miracle cure is longed for, and sometimes being offered at a steep price with a toothy smile.

Aloe And Its Medicinal Qualities

Along with its common use as a salve for mild burns and blisters (cut along the plump leaf and squeeze out the gel, which contains aloectin B,), a powder made from the sap, then mixed in water (the mixture is called bitter aloes for a reason and contains anthraquinones) can be used as a laxative or purgative. Most people just go to the drug store, but this is useful information if you are in the jungle and unwisely eat another, poisonous plant. Aloe grown outdoors has much more efficacy than plants grown on a window sill.

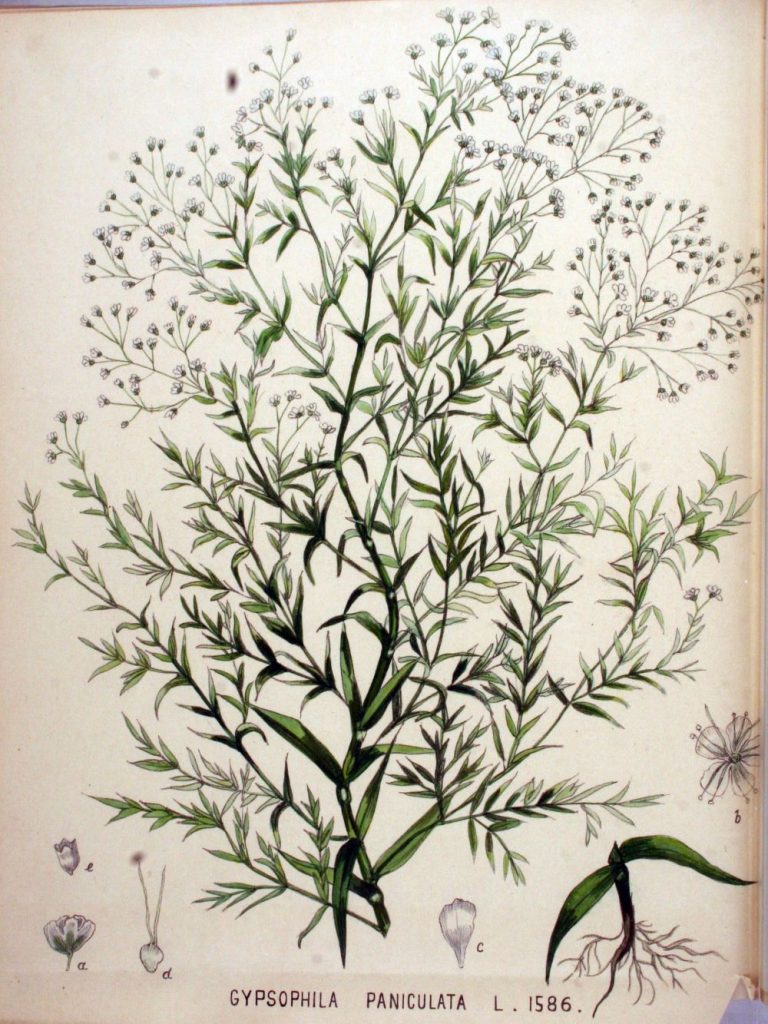

Gypsophila Paniculata – Baby’s Breath

How could something that is so small and delicate, and have such sweet associations be a purgative? Gypsophila panicula does indeed make people throw up if consumed. And that is a medicinal use.

Echinacea (Also Know As The Coneflower)

This beautiful flower, also known as the coneflower, a member of the daisy family, comes in vibrant colors and lasts forever in the ornamental garden. Starting in the 1980s, “everyone” was taking echinacea to prevent colds or reduce their severity. Since then there have been tests of echinacea’s efficacy not just in treating rhinovirus but also cancer. So far, evidence is thin, but there are still people who swear by it. Nevertheless, the flowers are pretty. The name, by the way, comes from the Greek word for “hedgehog.” Anyone who has touched the center of the head of an echinacea will understand.

Feverfew As An Analgesic For Aches And Pains

This plant found itself in competition in the early apothecary with salicylic acid (from willow branches) and meadow sweet. People as far back as the Romans used “feverfew” (t. parthenium asterales), which looks like a small daisy, or aster, and is an analgesic, which is to say it helps treat headaches, toothaches, and other pains, including cramps. Fevers, scientists now say, not so much. Women who knew how to grow, harvest and use feverfew were considered family healers, not witches.

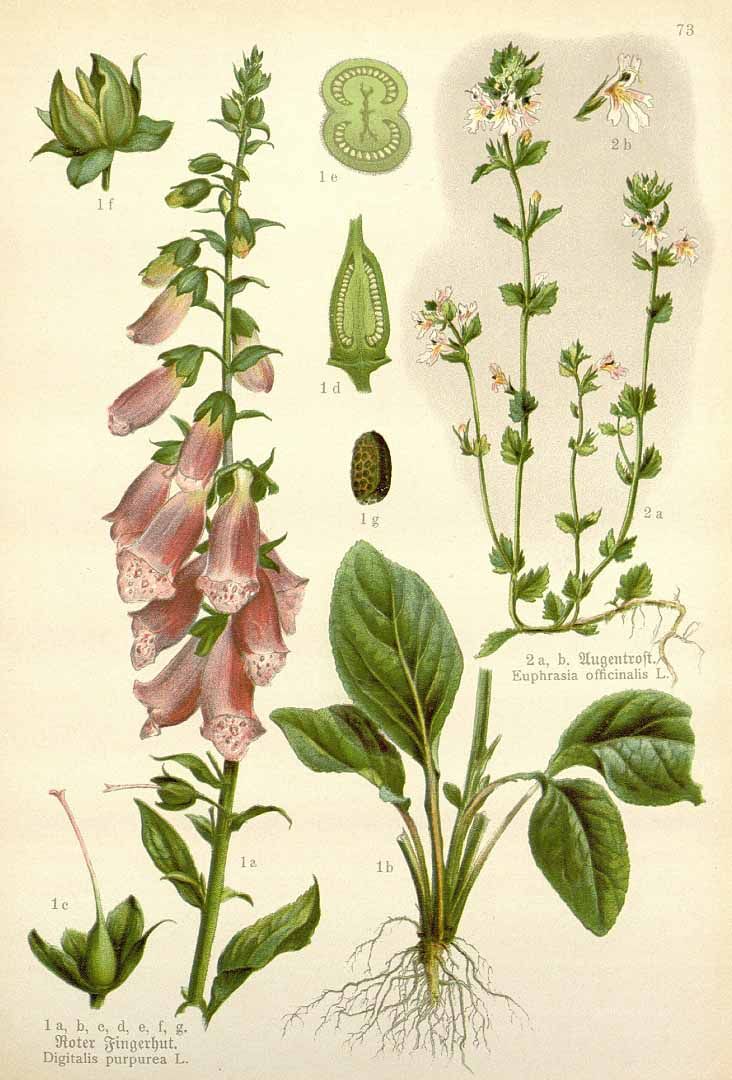

The Foxglove – Digitalis Purpurea

The old-fashioned foxglove is a star in the cottage garden. A biennial it grows one year, then blooms the next, drops seeds, and starts over. It’s kind of a game of hide and seek, and an old garden of foxglove will surprise you with new colors, new plants in different places, year after year. Of course, every part of the plant is poisonous.

And as the name might suggest the foxglove was the source of digoxin, and first used as a treatment in 1785. It helps people with congestive heart failure, and it helps people with atrial fibrillation. Digoxin, which is now manufactured, rather than derived from the plant. is a drug that stimulates the heart for innumerable people with weak or failing hearts.

I remember being shocked to see foxgloves stuck into a cake in a movie called “One True Thing,” starring Meryl Streep as a woman dying of cancer. The cake was being served to women gathered around a table. I was waiting for an ambulance to pull up, or for the movie to end abruptly, but apparently Renee Zellweger meant no harm sticking the flowers into the cake, and so in movie logic no one was killed.

Children have been poisoned just by drinking water that foxgloves have been sitting in. People are warned to wash their hands after handling foxgloves for a bouquet. And needless to say, it’s probably best to put a bouquet of foxglove on a mantelpiece or a hall table and not a dinner table, where someone might be inclined to reach out and touch one of the velvety bells.

The name of course comes from the old notion that a fox could slip his paws into the flowers. An expert in Anglo-Saxon folklore, Terri Windling, gives another derivation: “foxes-gleow,” a “gleow” being a ring of bells. “This is connected to Norse legends in which foxes wear the bell-shaped foxglove blossoms around their necks; the ringing of bells was a spell of protection against hunters and hounds.” June 2, 2019 “The Folklore of Foxgloves, Terri Windling

The Mandrake – Members of the Solanaceae Family

I am going to wrap a lot of flowering plants together under this heading. They include the henbane, flowering tobacco, datura (angel’s trumpet), belladonna (atropa belladonna) and even the tomato plant. They are all members of the Solanaceae family, and their biologically active alkaloids make most of them poisonous.

The tomato just tastes good, but when it was brought back from the New World, because it resembled its cousins, it wasn’t eaten for years, and grown merely as an ornamental, an oddity that Spanish explorers brought back from South America. Luckily for us, people around the Mediterranean let their curiosity and hunger get the better of them, and thus was born the pomma doro, and tomato sauce and the caprese.

But back to the ones that make medicine pharmacists use. Witches and sorcerers, alchemists, wise men and conjurers were the ones who knew how to use the members of the Solanaceae family (long before the tomato arrived in the Old World). Women, who picked herbs in the course of the day and passed on a vast folk knowledge of edible plants, and plants that were poisonous or tasted bad. In the long course of picking and experimenting, women discovered other uses for some flowering plants.

Often members of the Solanaceae family could be used in small doses to relieve pain, in large doses to kill. In between, in careful measure, and in combination, some of those flowering plants could be mixed with a fat of some kind to provide a spell. They especially valued hallucinogenic alkaloids, including scopolamina and atropine, the latter of which can be absorbed through the skin.

It is standard to think of doctors and apothecaries as the ones who made scientific discoveries. They were literate, and their discoveries were written down.

But it is now known that the women charged with being witches had discovered very specific recipes, some of them for those ointments and oils that could be applied to sticks and poles. Women (witches) would “ride” these poles, and the salves would be absorbed through genital tissue, underpants having not yet been invented. They were on trips, so to speak, in which many of them had ecstatic or sexual experiences. No wonder men of higher station wanted them punished. And husbands were afraid.

Let’s start with the one with the cool name, the Deadly Nightshade (Atropa belladonna), which has a tubular flower. If you’ve been to the eye doctor, you’ve benefited from this flowering plant. The drops the doctor puts in your eyes, atropine, come from the belladonna. Hundreds of years ago, prostitutes made the pupils of their eyes bigger, and more attractive, by using juice from the berries of the same plant.

Belladonna means “pretty woman” in Italian. The medical world has also invented an Atropen, a way of administering atropine in emergency situations where someone has been exposed to insecticide, or other organophosphate nerve agents. When a patient is wheeled in to the emergency room with a slow heartbeat, atropine is usually the drug of choice to increase heart rate, followed by epinephrine and dopamine.

Scopolamine, an alkaloid used to fight motion sickness and useful to counteract nausea from chemotherapy, can be rendered from Egyptian henbane (hyoscyamus muticus), another member of this family.

And from black henbane, or stinking nightshade. These henbanes, which originated in Asia, were known by the Egyptians, who mixed their leaves with cocaine to make a powerful anesthetic. Various plasters, poultices and infusions were developed. At one point it was an ingredient in beer, until it was replaced by hops.

Pliny the Elder in Greece said henbane was “of the nature of wine and therefore offensive to the understanding.” In other words, it left you confused.

It was used as a sedative and a pain killer. It was said that even smelling the flowers would cause sleep. Black henbane, you see, also had scopolamine, and some people rubbed the seeds behind their ears to prevent sea sickness. It is the ability of scopolamine to be applied on the skin that attracted (so it is believed) witches. Henbane is still used recreationally as a drug in India and parts of Africa. In India it is consumed as a drink. In Northern Africa it is smoked.

Seeds and leaves of henbane also carried hyoscyamine and atropine.

Hyoscyamine is used in medicine today to treat muscle cramps in the bowels (irritable bowel syndrome or IBS) or frequent urination, and other digestive problems. It can be used to treat the pain (excruciating) caused by kidney stones or gallstones, and some muscle problems related to Parkinson’s disease. It can also treat anticholinesterase poisoning, which is organophosphate (insecticide or nerve agent) poisoning.

But it must never be used with alcohol.

As you can see, the medical value of the henbanes (and the danger of overdose) has been understood for thousands of years.

We know that nicotine comes from the tobacco plant, and that flowering tobacco is commonly used as a tall annual in cottage gardens. Nicotine is also a useful tool in insecticides, and other agricultural uses. But nicotine also turns up in small amounts in its distant cousins: tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants and green peppers. These are trace amounts, to be sure, but nicotine knows where you are.

Datura metel, or jimson weed, can be found growing almost anywhere, its pretty white bells making it look out of place in trash heaps and along the sides of roads. Surely this is an important plant escaped from someone’s garden… But it’s not. Jimson weed was growing in Virginia when Sir Walter Raleigh’s men arrived, and one story has it that his men picked its leaves, dried them and smoked them. For several days they wandered away from the camp having explorers’ first bad trip in America. Cows eat jimson weed and wander around, confused, lowing. Eat too much of it, and death follows.

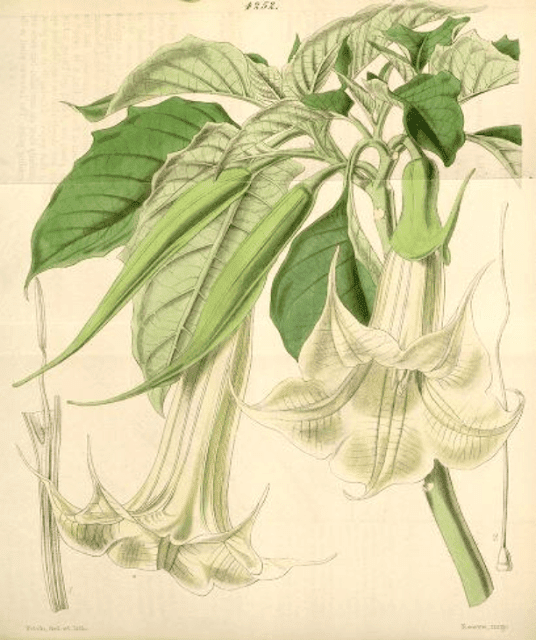

The highly cultivated form, Angel’s Trumpet or Brugmansia, (to be clear, Angel’s trumpets point down, Datura point up) is grown in gardens and can reach 10 feet high. None of it should be consumed, especially by children and pets. It too can be a source of the alkaloids mentioned above.

I pulled jimson weed out of a flower bed in Pennsylvania, chopped the roots out, bagged all the parts of the plant and the spiky seed pods and threw everything away. (There was a 5-year-old child in the home.)

I returned to that garden three years later, and there was a datura, blooming away, on the other side of the flower bed. The child was older, past the age of eating plants. I decided not to mention it. It looked pretty.

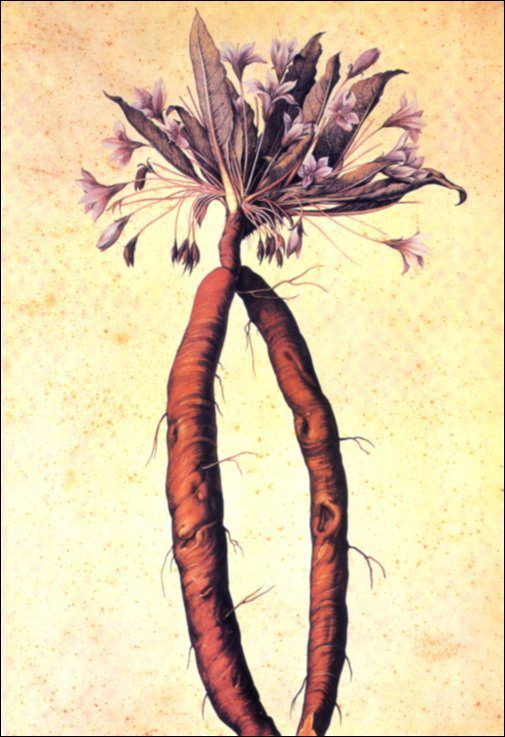

Now for the bad guy. Mandrake root, Deadly Nightshade. It’s all a matter of dosage, of course, but Mandragora is a killer. There were all kinds of folk tales about the root of the plant, mostly having to do with the fact that it looked like a person’s fleshy body. (If you have an active imagination.)

It was believed that it screamed when you pulled it out of the ground and cursed the one who pulled it out to death. The solution was to tie a dog to the root, and then call the dog. That way the root would kill the dog. (!) I would assume this method ended up with either no root, or a root and a living dog. So much for the theory. The flowers are funny looking, because they seem to sprout out of the ground without benefit of stalk. Most of what is going on is underground, where that fleshy root is developing. It’s the alkaloids that once again make the plant (not just the root but the leaves) poisonous.

In the Middle ages, when people were made of sterner stuff, and apothecaries knew a thing or two about dosages, it was considered a pain-killer and aphrodisiac. Amateurs out for a thrill discovered that the alkaloids in Mandrake root are anticholinergic, hallucinogenic and hypnotic. Those who have survived poisoning by mandrake say it is highly unpleasant. Not a good trip in any sense of the word. No one wants to try it a second time. The anticholinergic properties can lead to asphyxiation. And eating or drinking a concoction of mandrake root, if it doesn’t kill you, leads to vomiting and diarrhea.

In other words, a bar selling mandrake shakes would not have a lot of repeat business. Still, you will see various powders and potions on sale on Amazon for those who want to dabble. We advise buying a nice bouquet of lilacs or ranunculus instead.

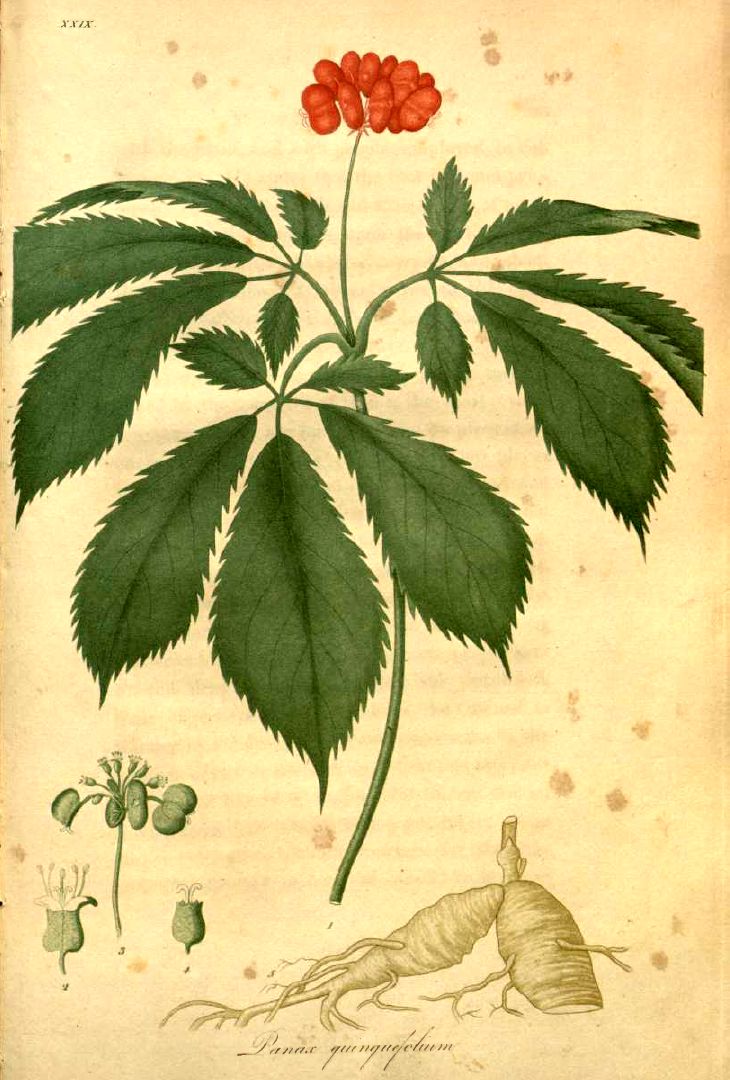

Panax Quinquefolia (Ginseng)

Here is where Western medicine meets Chinese medicine. When I asked a man considered to be the US expert on growing ginseng to send me the scientific medical research on ginseng efficacy, he said “You’ll have to read Chinese.” Generally speaking, ginseng is not for the young or the pregnant, the depressed or for anyone with a serious inflammatory disease. In Chinese medicine it is meant to prolong life and increase vigor. It (like nicotine) both relaxes and stimulates the nervous system. A course of treatment is not supposed to last longer than three weeks. The medicine, used to treat old age, lack of appetite, insomnia, stress, is made from the roots of the plant, harvested in the fall.

The researcher Debra Barton, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center in Rochester, MN cites experiments done in the lab and with animals that suggest ginseng “works as an anti-inflammatory or by controlling levels of stress hormones that the body.” The new study builds on previous work at the Mayo Clinic that showed that about one-fourth of people with cancer-related fatigue said they felt “moderately better” or “much better” after taking 1,000-milligram or 2,000-milligram ginseng tablets, compared with 10 percent taking placebo pills.

Here is another fact confirmed by Western medicine: the ginseng saponins (just think “antioxidants”) will slightly protect you from gamma irradiation.

Filipendula Ulmaria (Meadowsweet)

In the Middle Ages, in Europe, people treasured every part of a plant called Meadowsweet, at the time classified as “spiraea”: the flowers smelled good, leaves tasted good in stews; even roots and leaves felt nice underfoot, when the custom was to cover floors with rushes. When a German scientist discovered that Meadowsweet was a source of salicylic acid; he created a synthetic version and his employer, Bayer, deemed it “aspirin,” adding an “a” to the front of the word “spirsäure,” German for “spiraea.”

Meadowsweet also contains tannins (the same thing that is in red wine) which might reduce swelling, if you brew up a pot of meadowsweet, but now we are getting into folk medicine. Folk medicine also believed that the plant could settle an upset stomach, colds (which do eventually go away) and increase the output of urine (which, if you are drinking it in enough water, is sure to be a result).

The Peony – Paeonia Lactiflora Pallas

In China, Korea and Japan, a solution made with the dried root of the peony (but not the tough outside of the root) of Paeonia lactiflora Pallas, or the Chinese peony, is used to treat symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, hepatitis, muscle cramping and spasms and fever. According to a 2011 study in the peer-reviewed Frontiers in Pharmacology outlined tests done China with Paeoniflorin, the most abundant of the 15 components in the water/ethanol extract of the root known as total glucosides of peony (TGP). Paeoniflorin accounts for the pharmacological effects observed with TGP in both in vitro and in vivo studies.

The studies outlined numerous ways in which laboratory animals were stressed or caused pain and demonstrated how TGP reduced pain and stress. The paper attributed the effect to the adenosine A1 receptor. I could give you a lot of details about mouse paws, hot plates and mouse squeaks, but thought you might prefer hearing about adenosine A1 receptors instead.

Prostaglandins are a natural reaction to injury, leading to pain, inflammation, and possibly a barrier to healing. TGP, the paper suggested, inhibiting the production of prostaglandin E2 (which causes fever), leukotriene B4, and nitric oxide, and suppresses an increase of intracellular calcium ion concentration.

The tests remain done entirely on animals. And there has not been a great deal of excitement about studying peony root in Western medicine. But health food stores sell TGP with claims that it will extend life, ease rheumatoid arthritis, help with Sjogren’s syndrome (cold hands and feet), multiple sclerosis, any autoimmune disease, and, among other things, depression. The only known side effects are mild gastrointestinal disturbances and mild diarrhea.

Catharanthus roseus (Periwinkle)

Nothing could sound friendlier or less fearsome than “periwinkle.” It is more commonly known as vinca, a ground cover with tiny flowers. But the Madagascar periwinkle produces two ferocious cancer fighters, vinblastine and vincristine. A ton a dried periwinkle leaves makes one ounce of vincristine, which is effective against two kinds of leukemia, neuroblastoma, small cell lung cancer and others. Vincristine is on the World Health Organization’s list of Essential Medicines.

Vinca rosea, or in modern terminology Catharanthus roseus, is a main source of vinca alkaloids. Until science learned to synthesize these alkaloids, hundreds of acres in Texas were devoted to growing and harvesting periwinkle. So the next time you see vinca holding down a landscaped garden incline, just bow your head a little and give thanks. This sweetly-name little plant saves lives every day.

The Poppy (Papaver Somniferum)

We wear a crepe paper poppy on Veterans’ Day to remember those who lie in Flanders Field where poppies grow, row on row. But generations of military veterans and civilians have a different relationship to the poppy, and its natural derivatives, opium, morphine, codeine. The artificial pain killer heroin was synthesized by Bayer in 1889 and meant to be a safe substitute for morphine, which was being abused. Abuse of heroin followed, as well as even worse abuse of a pain-killing drug derived from an alkaloid in another poppy, oxycodone.

Poppy illustration 1445, Andrea Amadio. Biblioteca Marciana, Venice, Italy

Poppy illustration 1445, Andrea Amadio. Biblioteca Marciana, Venice, Italy

For millennia people worshiped the ability to ease pain of childbirth, of injuries in war, of surgery. Laws condemned people for using the same drug recreationally. Critics sometimes celebrated works of art by those same people for music, poetry, painting, writing. Judges put people in prison, countries outlawed the drugs. And then created new ones. The opium poppy (which also produces seeds for your bagel) has never stopped giving; but human frailty has led to a great deal of pain and thousands of lost lives.

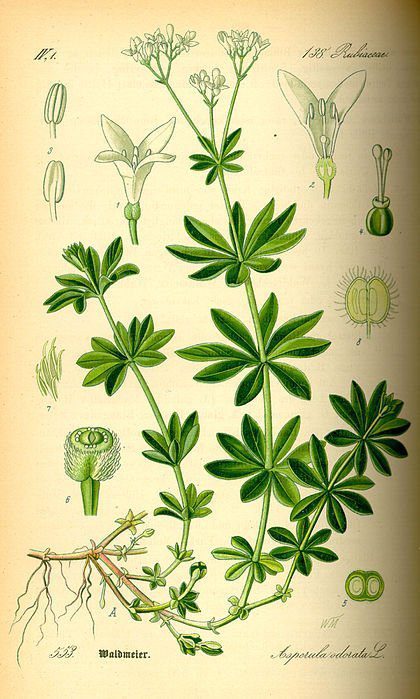

Rubiaceae Is Loaded With Alkaloids

This is another family loaded with alkaloids that people have learned to exploit. It includes kratom (a tree with yellow flowers), the coffee bush (you don’t get coffee beans without first having coffee flowers), woodruff, a member of the madder sub family, and Cinchona, flowering trees and shrubs. The bark of Cinchona yields quinine and other alkaloids that were once the only treatments against malaria when the British, French and Portuguese were colonizing Africa. Even now one Cinchona may be effective against a kind of malaria that is resistant to synthetic drugs. Caffeine, and we knew this, right, extends the effects of adrenaline.

Another plant in this family, Psychotria viridis, contains dimethyltryptamine, a psychedelic known as the “businessman’s LSD.” Because of its short-acting time, and a renewed interest in micro-dosing LSD, Psychotria viridis, which has been used in religious ceremonies among the Quechuan people in Peru, Ecuador and elsewhere in the Andes, may become a paying crop. (Psychotria is one of the largest families in all of botany, and much remains to be studied.)

Mitragyna speciosa is another Rubiaceae plant that takes people on a trip. There’s a recent vogue for kratom to the point that rehab facilities in Florida (why does it always have to be Florida) offer to wean people off heroin and oxycodone with kratom tea. The problem is that people become addicted to kratom, which contains the alkaloid mitragynine, which is like the much touted African psychedelic Yohimbine, but as a kappa-opioid receptor agonist (remember, an “agonist” is a helper) is roughly 13 times more potent than morphine.

Sweet Woodruff is a member of the Rubiaceae (madder) family, which includes coffee and gardenias. Sweet woodruff contains coumarin, which is used as a blood thinner for people with a tendency to grow clots in their veins, leading to stroke or heart attacks.

Coumarin is also marketed as Warfarin, a rat poison. Rat livers cannot process coumarin, and they bleed to death internally. So coumarin, which is also found in the tonga bean and several other plants, has been a life saver for people and a valuable control for rats, especially in cities. (In the country, farmers still rely on cats and terriers.)

The name “ipecac” comes from the plant in South America, Carapichea ipecacuanha, another member of the madder family. Ipecac is a syrup in the nanny’s war chest, to make a child throw up if she has eaten something poisonous (as long as it is non-caustic). The madder family, in other words is entire array of proper drugs. I will explore this family much further.

Chinese or Herbal Medicine

Finally, joining this amazing family of coffee, psychedelics, malaria fighters and blood thinners is the use of tisanes, infusions, teas and herbals medicines, which many people swear by. There is no doubt people are helped by the ministrations of someone guiding them through their illness. But results are not always proven scientifically.

Consider the gardenia, which in Chinese medicine is said to cleanse the blood. But what does “cleansing the blood” mean, and how can you tell? Many claims of herbal medicine are subjective and subjunctive, with words like “may” or “might” and “helps” or “leads to.” Chinese medicine says the gardenia “deals with bladder problems and physical injuries.” It is said that it “helps alleviate depression, stress, anxiety, insomnia and similar disorders.”

In pioneer days, snake oil salesmen held up medicine bottles that promised to cure everything from hangnails to hernias to cancer. They usually contain quantities of either alcohol or cocaine. Perhaps that helped.

What we can say about oil of the gardenia is that it smells great. Isn’t that enough?