Why Is Christmas Red and Hanukkah Blue?

By Linda Lee

When you think of Christmas, one thinks of poinsettias. Red poinsettias.

How did this tradition happen?

A Mexican legend tells of a girl who could only offer weeds as a gift to Jesus on Christmas Eve. When she brought the weeds into a church, they blossomed into the beautiful red poinsettias – now called Flores de Noche Buena in Mexico (Spanish for “flowers of the holy night”).

According to writer Sam Abramson, the plant is named for the first U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, Dr. Joel Roberts Poinsett, who introduced America to the poinsettia in 1828, after discovering it in the wilderness in southern Mexico. Dr. Poinsett, who dabbled in botany when he wasn’t politicking between nations, sent cuttings of the plant back to his South Carolina home. Over time, it became linked to Christmas.

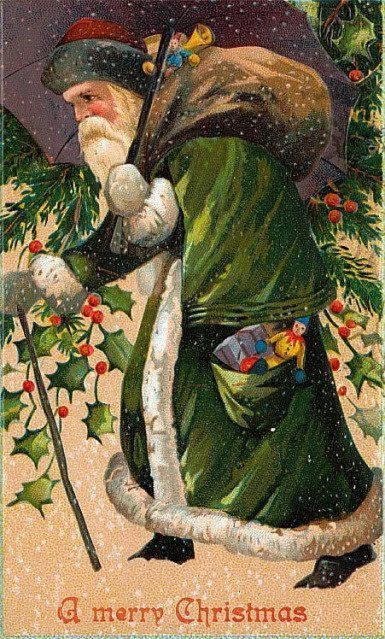

Bu then we have to wonder why is red the Christmas color? Illustrations from as recently as the 19th century portray Santa Claus dressed in green, or blue! Coca Cola did not invent a jolly Santa dressed in red in the Coca-Cola ads in 1931, with colors to match its logo, as NPR and others have claimed. There were other Santas dressed in red in illustrations and in ads before that. It took a while, however, for red to settle in as the accepted Christmas color.

It started with northern Europe and red holly berries, as well as the tradition of decorating evergreen trees with apples. (Apples store well in barrels; they look pretty on a tree, plus there was this thing about Adam and Eve and the forbidden fruit that was somehow mixed up with December.)

But how did northern Europe dictate the colors of Christmas? Credit the Dutch in America, Dickens and Queen Victoria, and the Germans. Until a few hundred years ago, Christmas was not a major holiday. It was a normal part of the ecclesiastical calendar. Note that Christmas did not begin or end the calendar year …

In central Europe gifts were sometimes given on St. Martins Day in November, or St. Nicholas Day in early December. Towns in Europe had winter markets with a few wooden toys and extra food for the cold days to come and the celebration of the pagan festival of Yule, which started at the winter solstice. In the 16th century Martin Luther swung his vote away from celebrating saint days (too Catholic) and toward the Christkindl, the Christ Child, who would bring gifts at Christmas time. It took a while to catch on. Nuremberg began having Christkindlmarkts in the 17th century and the idea spread to the rest of Germany. These days there are festive street fairs all over Germany that specialize in local food and handicrafts, especially wooden toys painted red and green, paper stars, tin ornaments, baked goods and marzipan.

Then there were the powerful and wealthy Dutch, the Frisians, the Flemish, some French from the north, Limburgers, Luxemburgers… people from that northern belt, including some northern Germans: all of them had a particular fondness for St. Nicholas, the patron saint of children. St. Nicholas was a bishop, so wore a red cape and a white robe. He had a bishop’s mitre (hat) and a long white beard. He was called Sinterklaas in Dutch, and Sankt Nikolaus in German. (Have you ever wondered why we had two different names for the guy? Santa Claus and Old Saint Nick?) The Dutch brought their traditions to the New World, especially to New Amsterdam, which became New York City: little treats for children, like candy left in their shoes, sometimes in their stockings, gifts from Sinterklaas, on St. Nicholas Day. Eventually the Dutch became Americanized, and moved their date to the American one Martin Luther preferred: Christmas. The Dutch gave us the word “koekjes,” cookies, too, and where would we be without Christmas koekjes?

Dickens came along and wrote “It’s good to be children sometimes, and never better than at Christmas, when its mighty Founder was a child himself.” Dickens wrote about Christmas in many other books and stories, but his “Christmas Carol,” published in 1843, seemed to seal the deal on Christmas, at least to describe families gathering and eating goose and Christmas pudding, if they were lucky. His focus was on children, presents and concern for the poor and less fortunate. Also ghosts and death.

So Victorian England cemented our notion of what made up the rest of Christmas. In 1861 Queen Victoria married her beloved Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and because they were so popular as a couple, they popularized all those German traditions that were already in the English royal family. (Victoria’s royal grandmother was German.) The royals brought in an evergreen, decorated it and sang carols. Now it was just bigger and better. A new tradition was sending Christmas cards, thanks to the penny post. Presents were similar to the ones Prince Albert had in Germany, traditional wooden toys and ornaments, painted green and red, the traditional German colors for Christmas.

And so that is how red became the color of Christmas: because of Sinterklaas’s red cape and white beard, all those German toys, and the fact that red goes well with Christmas trees, a German tradition left over from the celebration of Yule, because evergreens symbolized life in the middle of winter. Red and green are also complementary colors on the color wheel, and look good with white.

When the poinsettia was tamed from a cut flower into a potted plant, and became a holiday staple in the 1960s, the association of Christmas and red was complete. Of course, plant breeders have now figured out how to breed yellow poinsettias, and green ones, pink and magenta. But red still looks right.

The colors for Hanukkah are blue and white, the colors of the flag of Israel. Of course the question then is why blue? It’s the color of a thread the Israelites were told to dye the thread on the knotted fringes of their prayer shawls with this “perfect blue” made with ink for a sea snail. The blue is a little deeper than the classic blue Pantone selected as its color for 2020. The Jewish religion prefers that people make contributions to a charity rather than send flowers to a funeral. And there is no customary Hanukkah flower, but white lilies and carnations with blue delphiniums would be suitable. – Linda Lee

Photo credit, Sinterklass, Sander van der Wel