In Honor of Presidents Day, a Look at Jefferson and Washington’s Gardens

Presidents’ Day is a federal holiday celebrated on the third Monday in February. According to history.com, it was originally established in 1885 in recognition of President George Washington, whose birthday was February 27, 1732. However, the holiday became popularly known as Presidents’ Day after it was moved as part of 1971’s Uniform Monday Holiday Act, an attempt to create more three-day weekends for the nation’s workers.

While several states still have individual holidays honoring the birthdays of Washington, Abraham Lincoln and other figures, Presidents’ Day is now popularly viewed as a day to celebrate all U.S. presidents, past and present.

To celebrate this holiday, we are sharing Linda Lee’s story on the Founding Fathers and their love of gardens. Enjoy.

By Linda Lee

Thomas Jefferson, George Washington and Alexander Hamilton were farmers, as were most men of their time – even if they became soldiers, lawyers and statesmen. Benjamin Franklin, seated at center in the above painting of the Second Continental Congress, was a scientist with a deep interest in seeds as a source of American self-sufficiency. John Jay, who was president of the Congress and navigated many essential treaties, retired to life as a gentleman farmer in Westchester.

They were knowledgeable about plants, including flowers, and four of them knew the Philadelphia botanist John Bartram and ordered plants from him. Outside of their occupation of the White House and higher reaches of public service, each of them had farms or estates with flower gardens. In Franklin’s case, it was the garden behind his townhouse in Philadelphia, perhaps best known for his mulberry tree, under which details of the Constitution were hashed out.

To maintain their legacies, their flower gardens, are maintained today to honor the men who shaped the United States of America. As Thomas Jefferson once noted, “Too old to plant trees for my own gratification, I shall do it for my posterity.”

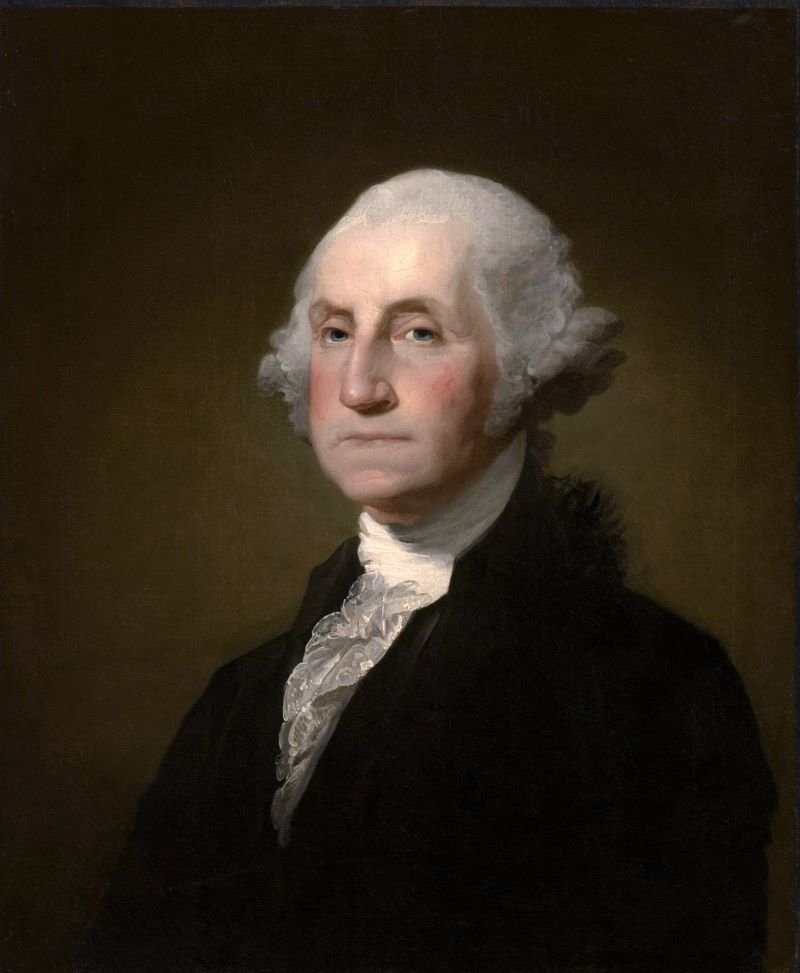

George Washington’s Pleasure Garden at Mount Vernon

Washington’s greatest interest may have been manure; he once had his workers and slaves set up ten experimental boxes with different kinds of manure, and declared horse manure the best, and chicken manure the “hottest.” He also created innovative ways to heat his greenhouse which housed tropical plants that he collected.

Of course, he is credited with the famous story of “I can’t tell a lie,” in a mythic tale about him cutting down a cherry tree. It was created by biographer Mason Locke Weems’ biography, The Life of Washington, in 1800. But he did love trees. His real favorite? According to horticulturist Dean Norton, willow trees were the most popular at his Mt. Vernon home. He also loved lilacs.

We do know that, as the owner of Mount Vernon and other plantations, he was expected to have a pleasure garden, including African marigolds, seeds for which were being sold in the Colonies as early as 1730, Brown-eyed Susans and “Basket of Gold” (Aurinia saxatilis), below, a ten-inch tall perennial that lined garden paths. Because he ordered trees and plants from John Bartram in Philadelphia, it is likely he ordered from Bartram’s amazing nursery list in 1792, preserved in government archives.

It included a rhododendron with large rose-colored flowers, three types of viburnum, Mock orange “a sweet-flowering shrub,” a kind of wisteria he said was “a rambling florobundant climber,” hydrangea and what Bartram called hibiscus, and is now called scarlet rose mallow. (We know Thomas Jefferson ordered it for his garden; even in 1792 Founding Fathers were not immune to a nursery description like “a most elegant flowering plant; flowers large, of a splendid crimson colour.”)

According to experts at Mount Vernon. favored flowers including Crown Imperial, fritillaria imperialis.

In fact, in 1784, the Marquis de Lafayette requested seeds of this plant from Washington. He also liked Love-in-the-mist, a common garden flower in Europe in the 18th century, Absalom tulips, and oleander. Yes, he grew hemp which was made for rope. And here’s a sweet touch. In 1794, he ordered artichoke seeds for his wife Martha and grew them.

Washington lived only two years after stepping down as President, but his career as a successful general and important land owner before he became president marked him as a person who merited visits from dignitaries, although he far preferred sitting at home with Martha and reading.

One visitor to Washington’s home remarked on a visit to his pleasure garden that it had a “great variety of plants and flowers, wonderful in appearance, exquisite in their perfume and delightful to the eye…” In fact, his pleasure garden was kept narrow in deference to vegetables, fruit, and croplands. But the flowers were paid attention to and Washington did indulge in a rich man’s greenhouse, where he could grow rare and exotic plants and flowers, grapes and orange, lemon and lime trees. Putting orange blossoms on a dinner table certainly would have been a coup.

For years the groundskeepers at the Mount Vernon National Park laid out the Upper Garden as a formal garden with boxwood and a rose garden as if Washington might have been a French king. It was only in 2010 that deep horticultural research revealed that no such boxwood existed in that place at Mount Vernon.

Instead, Washington planted his flowers around the outside of his Upper Garden vegetable gardens, the garden closest to the house. In other words, his pleasure gardens were along the pathways surrounding his working kitchen gardens, which is what the upper gardens now look like at Mount Vernon.

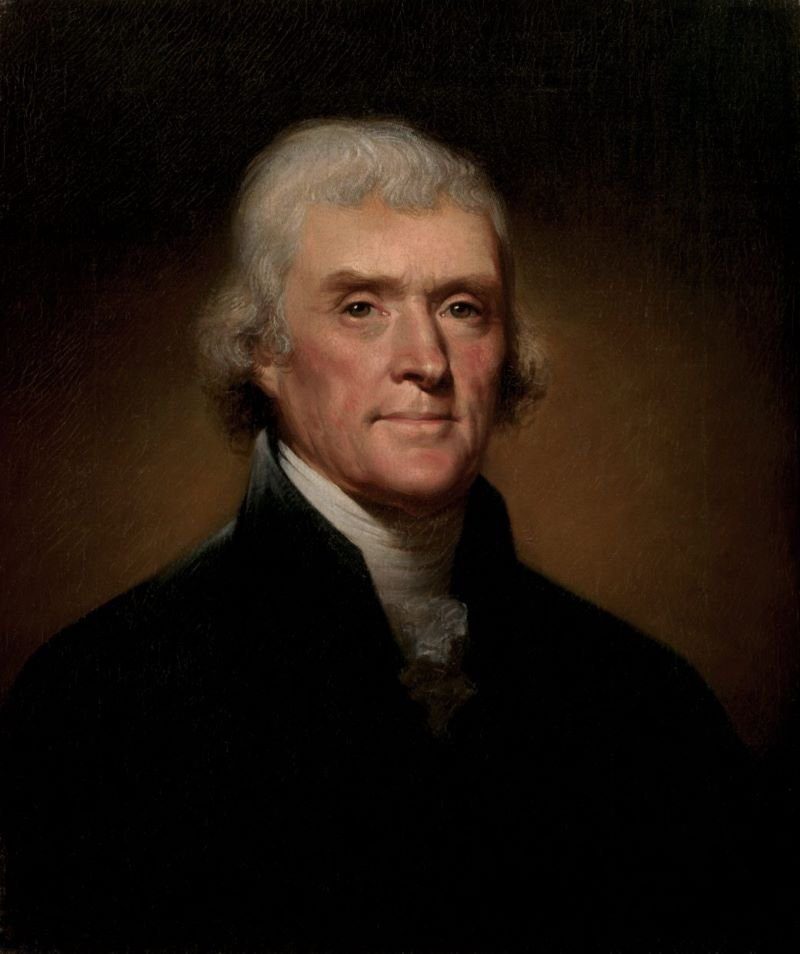

Thomas Jefferson, The American Polymath

Jefferson, the nation’s third President, knew a great deal about many things: astronomy, diplomacy, music, science, architecture, agriculture, politics, books and botany. And that is not a complete list. The nation’s third President, after Washington and John Adams, Jefferson introduced geraniums, a plant new to America, into the newly built White House. He graded and planted the South Lawn, which had formerly led to a swamp and is now known for its ceremonial splendor and Easter egg rolls.

Jefferson was, of course, a passionate horticulturist. He had inherited Monticello, one of his three estates in Virginia, when he was 26, in 1770, and begun siting and designing the house and gardens then. Specimen shade trees, nut and fruit trees were always the first consideration, along with grading and landscaping the grounds.

Within two years he was married. But within two more years, political life drew him to Philadelphia, where he was the Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress. His ability as a writer, lawyer and thinker propelled him into public life as an author of the Declaration of Independence, Governor of Virginia, Minister to France, Secretary of State, Vice President of the United States, and President from 1801 to 1809.

Because the White House was new, and the first Presidents were but temporary residents, they set about planting trees for the future. The 18 acre grounds around the White House soon included fruit trees and species that represented the states in the Union. Of necessity, there were vegetable gardens around the White House, which had a staff to support, and visitors to entertain, even in a muddy construction zone.

Not until the sixth president, John Adams’s son John Quincy Adams, were formal flower gardens planted, between 1825 and 1829. By then Washington was becoming a more suitable setting for the nation’s capital.

In Jefferson’s time, in 1801, Washington was part swamp, and not nearly as fashionable or convenient for most politicians as Philadelphia had been. Only the North Wing of the Capitol Building had been finished, and funds were non-existent for further work. Summers in Washington were notably torrid and many, even Presidents, were eager to get out of town. The House of Representatives was meeting in a temporary building they called “the Oven.”

In 1801, legislators from New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Vermont had even further to go to reach Washington, and complained bitterly. Laws had to be passed to compel attendance during legislative sessions.

Thus, the federal government was not a full-time occupation. Most members of Congress were still landowners and needed to get back to their crops and livestock. In 1801, Congress met from December to May 1, 1802. In 1802, from December to March, 1803.

For Jefferson, Monticello was 120 miles south, perhaps two days away and up in the cool mountains. He never stopped working on improving, or monitoring the planting and planning there, which included work by slaves. We have to remember that much of the building of these great plantations and estates, even the buildings in Washington, was done by slave labor.

We know that Jefferson sent seeds back to Monticello when he traveled abroad. And when he returned to the states he ordered seeds from abroad and traded seeds and plants with friends. In fact, he sent plant specimens to Hosack for Hosack’s Elgin Botanical Garden in New York. In return, Hosack made Jefferson a member of the New York Horticultural Society along with John Adams, James Madison, John Jay and the Marquis de Lafayette.

One of Jefferson’s dearest acquisitions was in 1811, from a gardener in Paris, the Painted Lady sweet pea, a genetic sport from 1737 that produced beautiful two-toned pink-and-white flowers, and had a lovely smell. Jefferson was always one to appreciate double benefits in plants.

There are books written about Jefferson’s gardens, some of them devoted to unraveling Jefferson’s sometimes idiosyncratic names in his garden diaries. He was known to create names on his own, like Pentapetes Phoenicia.

Along with Bartram and Hosack, Jefferson had his own nurseryman and garden mentor, a man named Bernard McMahon, who was based, like Bartram, in Philadelphia.

Jefferson was a devotee of McMahon’s “The American Gardener’s Calendar,” which listed chores month by month. It was published in 1806 and appealed to Jefferson’s orderly and scientific mind. Jefferson wanted McMahon to accompany Lewis & Clark on their expedition of the new Louisiana Purchase, in 1803, which would more than double the territory of the United States, and make Louisiana a state in 1812. McMahon begged off, saying he was too frail for such a rigorous trip.

Plants, gardening and nature, it seems were a deep part of Jefferson’s inquiring soul.

He wrote to a friend, two years after he left office: “I have often thought that if heaven had given me choice of my position & calling, it should have been on a rich spot of earth, well-watered, and near a good market for the productions of the garden.”

He closed by saying, “but tho’ an old man, I am but a young gardener.” He was 68, and lived to be 83.