The Ikebana Floral Show at Kitano Hotel Celebrates Tradition

Over 30 floral artists contributed their talents to an ikebana exhibition hosted by New York City’s Kitano Hotel. The Japanese-style hotel, near Grand Central Station, has two annual flower shows for both the fall and spring seasons that the public can visit. In light of what took place in Japan, perhaps we can honor this tradition which teaches lessons of life through all its cycles.

Ikebana, which translates to “making flowers alive” or “way of flowers” is a Japanese tradition that dates back to the 7th century when floral offerings were made by the priests at temple alters. It then evolved to be a widespread tradition for the merchant and samurai classes with interesting applications.

“The samurais would fight and then go to have tea and learn to arrange flowers,” says Beverly Hashimoto, president of Ikebana International New York. “At these formal tea ceremonies, they would remove their swords before entering the tea house to engage in peaceful activities.”

In fact, all of Japan’s most celebrated generals were masters of ikebana finding it, as Hashimoto says, a form of “meditation” to calm the mind and clarify thoughts. Warriors like Hideyoshi and Yoshimasa, two of Japan’s most famous generals, said that ikebana was valuable training for the “masculine mind.” Hence, men, as well as women, were devotees of all things floral in Japanese culture, a memo more cultures should adopt.

Fortunately, ikebana could have been contained just in Japan if this art form didn’t have an American champion post World War II. Ellen Gordon Allen, the wife of a U.S. general, thought it would be a good idea to form an ikebana organization to introduce the world to Japan’s peaceful side through their reverence for flower arranging. (It was the wives of U.S. and Japanese officials who improved U.S.-Japanese relations by offering Washington D.C. cherry blossoms).

Thanks to Ellen Gordon Allen’s efforts, there are now thriving ikebana chapters around the world.

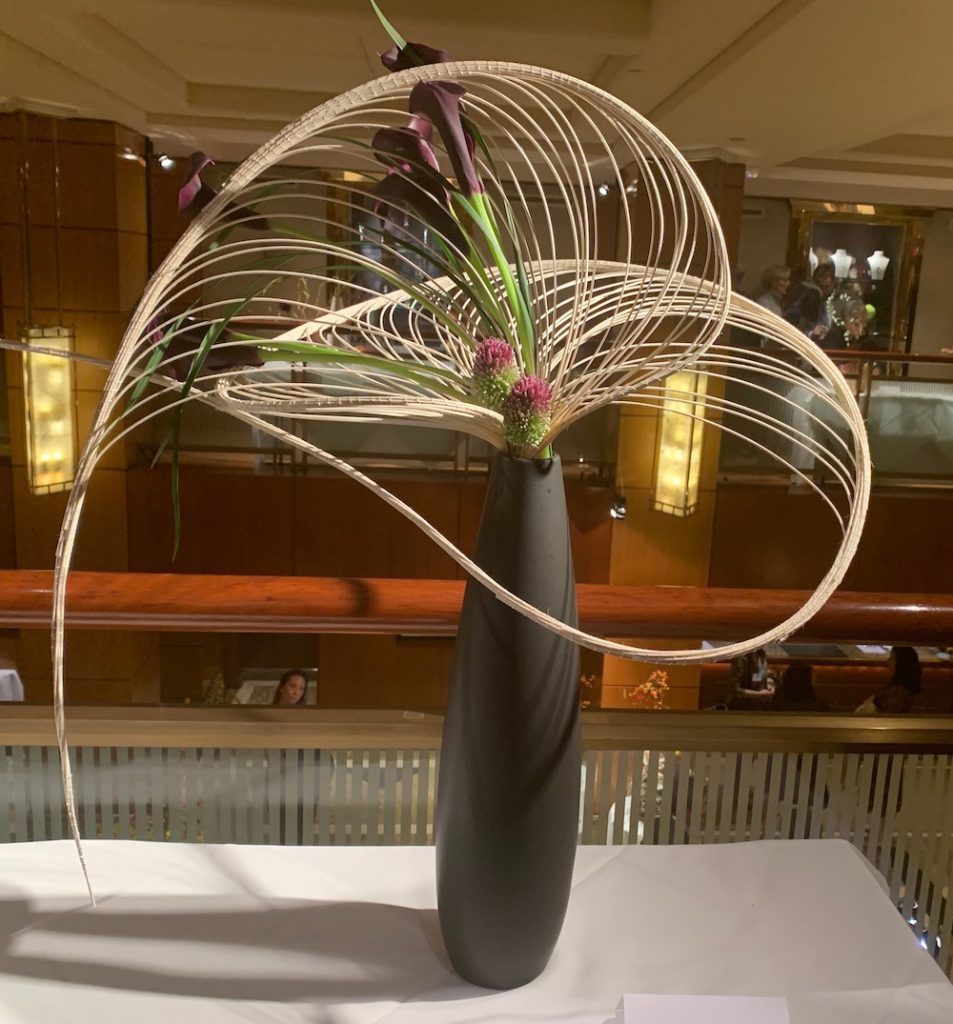

What most appeals to me about this ancient approach is that it looks at floral arrangements as landscapes that represent nature. “There is always air in the arrangements, an emptiness that also has its beauty,” explained Noritaka Noda, a master practitioner of Ikenobo, the most classic and oldest school under the ikebana umbrella. A branch that extends beyond the horizon, he points out, expresses continuity as is seen in this arrangement by Yuri Ishizuka as well as Masako Onoda.

Another appealing component of ikebana is that the artists will try to incorporate flowers that represent the cycles of life – past, present and future. Or as Beverly Hashimoto corrects me, “yesterday, today and tomorrow.”

In this arrangement by Marie Jeanne Lemarquis, from the Sogetsu discipline which is more avant-garde, the clematis stamens survive representing the past.

“A bud that has not bloomed can represent the future,” adds Beverly Hashimoto. Obviously the present is a flower that is in full bloom.

Hashimoto’s arrangement used dry coneflower seed heads to represent the past of summer. Since the arrangement is a glorious look to fall, she used mums and celosia in autumnal colors.

“Instead of greenery, I used burning bush and maples and a persimmon branch,” she explains.

Another concept is thinking of flower arranging as triangular spaces. In ancient Japanese, there would be small alcoves in homes that were ideal for these styled flower arrangements.

Although Noda’s weekly floral arrangements at the hotel are more elaborate, like the one below, he chose to create one that invoked this past use. It was both effective and simple. Less can be more. This arrangement evokes a serenity that is pleasing to the eye without being too distracting.

One of my favorites was a piece from Nobue Sandoz from Sogetsu and Deborah Hidajat’s work which is from the Ryusei school. The air in between these wood stalks is like swirling wind.

But this would never be part of an Ikebono arrangement. Why? Any wiring to mold the branches must be discreet and not too visible. The Sugestsu school allows the artist to use the wire as part of its decor as does Ryusei.

Mika Tanamura’s arrangement screamed fall with its clever use of birds of paradise as well as fresh peppers. Shigeno Okamoto’s arrangement also had a vibrancy that captivated with eye-catching orchids.

We all know how flowers make people happy. Another lesson to learn from this philosophy is that one doesn’t need too many flowers to create beauty. Often with just four or five flowers, one can create something memorable and delightful. There were no winners or losers at this contest since the displays aren’t judged. They exist solely to bring joy by masters in their field of study. – Jill Brooke

Jill Brooke is a former CNN correspondent and editor-in-chief of Avenue and Travel Savvy magazine. She is an author and the editorial director of FPD.

Photo Credits: FPD