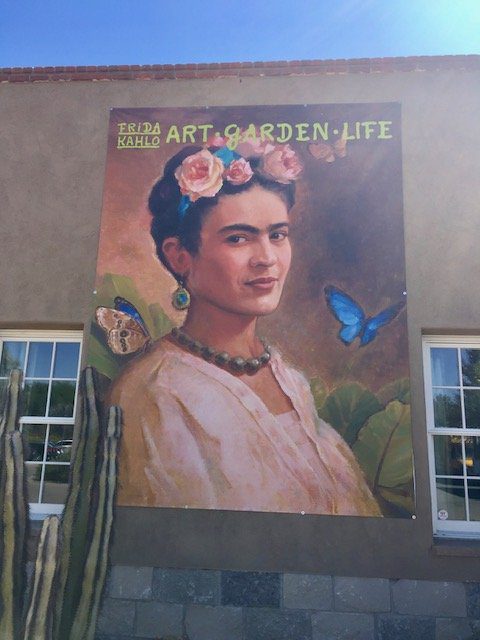

Frida Kahlo Exhibit Will Be at Brooklyn Museum Until May

Flowers Heal and Sometimes Wound.

Frida Kahlo has morphed into a heroine for every wounded minority and spurned spouse. The show that opened recently at the Brooklyn Museum: “Appearances Can Be Deceiving,” the largest in ten years devoted to her life and art, is sure to draw crowds, even though it shows only ten paintings. It does, however, offer insights into her private life, with photographs, including a color portrait of her shot by Nicholas Muray in Greenwich Village that looks like one of her paintings, and an intimate display of her belongings from Casa Azul in the Coyoacán section of Mexico City.

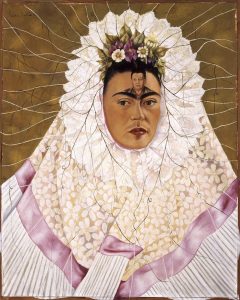

Confined to bed after a near-fatal bus crash (one wall displays her braces) Kahlo took up painting. Although famous for her self-portraits, her work was entwined with nature and flora and the symbolism attached to it.

In her self-portraits, she often wore pink bougainvillea wrapped into her braided hair; floral motifs adorned her native clothing. That was her signature style, even though sophisticated Mexican woman by the 1930s and 40s were gravitating to more Westernized ensembles. Native flowers like salvias, marigolds, dahlias and cannas appeared also in her art.

In her self-portraits, she often wore pink bougainvillea wrapped into her braided hair; floral motifs adorned her native clothing. That was her signature style, even though sophisticated Mexican woman by the 1930s and 40s were gravitating to more Westernized ensembles. Native flowers like salvias, marigolds, dahlias and cannas appeared also in her art.

“I paint flowers so they do not die,” said Kahlo.

Kahlo took pride in Mexico’s culture and history, from its ancient civilizations to the Revolution, which began in 1910. Painting flowers from her garden was one way she expressed these values on her canvases, since they were symbols of her heritage.

In a Financial Times article, Robin Lane Fox shared an insight into one of her most significant canvases, the 1940 “Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird.” It was on display at the New York Botanical Garden in 2015, when they also recreated Frida Kahlo’s garden at Casa Azul.

“Above a necklace of spiky shoots, which are drawing drops of blood from her neck, a pet monkey plays with one end of it, while a cat sits on her other shoulder. A hummingbird, an old Mexican charm for restoring love, hangs from her necklace’s loop,” he writes. “Flowers of fuchsia and a zinnia, two Mexican plants, are merged with insects’ wings in the bold green leaves on either side of her dark hair. This portrait dates to Kahlo’s brief, but painful, divorce from Diego Rivera, the giver of the pet monkey.

“But unlike feminist critics, I do not see the monkey is causing the necklace to draw blood from her neck. Experts at the [Botanical] garden have now identified it as a necklace of bougainvillea. In their greenhouse display, I noted how a bougainvillea’s mature stems are indeed thorny. Through a gardeners’ eyes, one of the century’s great self-portraits can be better understood.”

Once again, flora tells a story. In the language of flowers, love must have thorns along with the rose — or in this case — the bougainvillea. Not sucking one’s lifeblood, but declaring the reality that love has its seasons, withering and sometimes blooming again.

The exhibition was previously at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. A few years ago, there was also a fantastic exhibit of her garden at the Botanical Garden, that also traveled to Tuscon, Arizona where I saw it. This exhibit, like the one in New York, attracted record crowds.