Alfombras, Making the Flower Carpets of Holy Week

By Linda Lee

The making of flower carpets, alfombras, is a delightful aspect of Holy Week in devout Catholic parts of Latin America, Spain and elsewhere. The beautiful colonial city of Antigua Guatemala is especially renown for its Semana Santa, or Holy Week, customs.

La Antigua, highly regarded as a place to learn a pure Spanish accent because of its history as a seat of Spanish rule in Central America, is a World Heritage site and tourist destination.

La Antigua lay in ruins for nearly two centuries after a series of earthquakes moved the machinery of government in 1776 to a new location in Guatemala City in a less earthquake-prone area.

The restored ruins are now language schools, hotels and restaurants. While Guatemala itself is notoriously dangerous and poor; La Antigua thrives on agriculture, its languages schools, tourism and its reputation for relative safety.

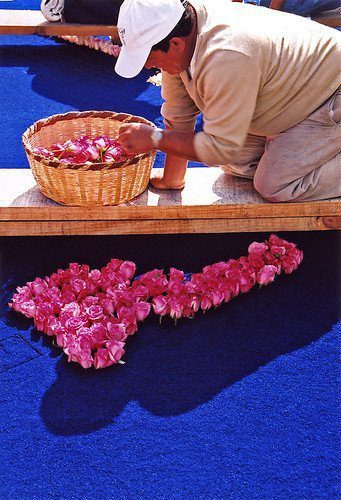

Thus the flower carpets, amateur works made throughout Lent, have been widely photographed. Although they are called flower carpets, many are made of custom-dyed sawdust or sand. The intricate patterns – some depict the Last Supper, parrots, oriental carpets or butterflies, a significant symbol in Mayan culture – are not for the most part created on site but the result of yearlong carving of wooden stencils.

An entire neighborhood, or a local hotel or restaurant, might sponsor a particularly talented young designer. The work can take a week to make, and passers-by carefully walk alongside the carpets until the announced day of a procession.

Even on the night before a procession – Antigua Guatemala knows a good thing and has processions on Sundays and Fridays in different church neighborhoods during Lent as well as the large ones on Good Friday, Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday – streets are filled with families finishing carpets.

Children do edges and spray water on sawdust to keep it from blowing away. Sand designs are the most refined. Sawdust is a little furrier. Flowers are the most tactile. No one seems concerned about tripping.

The flower carpets combine the welcoming of Jesus to Jerusalem, when palm fronds were laid before his donkey, with the celebration of his resurrection from the tomb on Easter Sunday. The flowers, celebrants say, show their welcome to the floats, called “andas,” which carry heavy carved figures of religious significance.

The floats are born by 40 to 60 “penitents,” who consider carrying this burden a way to make up for sins of the previous year. On Holy Saturday, while Jesus’ body lies in the tomb, before resurrection, women wearing black mantillas sometimes carry a float bearing a carving of Mary to a church.

The women’s float is carried by approximately 40 women in Antigua, Guatemala.

The women’s float is carried by approximately 40 women in Antigua, Guatemala.

The men often make a great show of staggering under the load of their float, walking slowly forward, hesitating, even leaning back before moving forward again. Sometimes the penitents, also called “cucuruchos,” or “bearers,” set the floats down on their wooden legs to rest before proceeding to the churches.

There are three primary churches in La Antigua: San Francisco, La Merced and Escuela de Cristo, and each sponsors many processions.

Nothing stops the processions. On Good Friday the full pageantry is hauled out: men dressed as Roman centurions, guards on horses, bands playing dirges on Good Friday. As the processions move down the street, the flower carpets quickly disappear.

All that work, all that beauty, is swept away by purple robes and scuffed under heavy boots.

The Semana Santa processions have arrived with their pageantry and the real message: life, death and life again.

Click!