The 10 Best Cherry Blossom Trees to Know and Love

By JILL BROOKE

Like siblings in a family, there are many different types of cherry trees to know and love. Since the National Parks Services takes care of the 3000 trees that launch spring in Washington D.C., here is their tutorial on the trees.

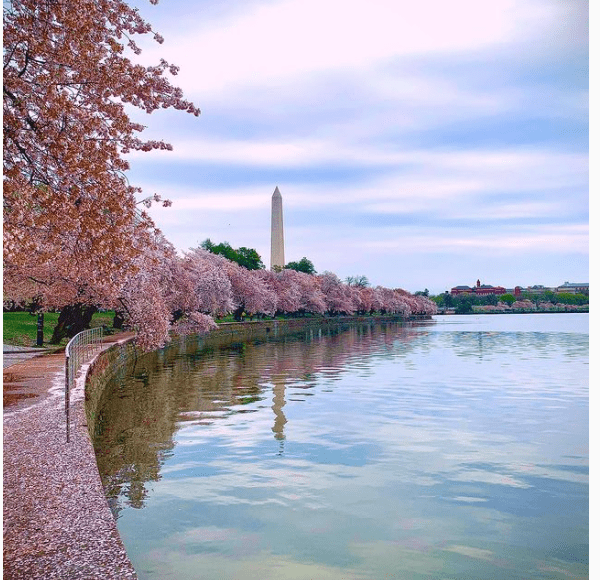

The famous cherry blossom trees along the Tidal Basin were originally a gift from Japan to the U.S. in 1912 as a symbol of renewal and friendship.

As part of the National Cherry Blossom Festival, in Washington D.C. there are many inspired cherry blossom activities including art shows, live performances and lectures from March 20-April 3. Those who can’t be in D.C. can view the Tidal Basin and cherry blossoms at peak bloom with the return of the #BloomCam, supported by Trust for the National Mall. Plus as we share later, there are other festivals worth knowing.

After all, cherry blossoms are truly special for many reasons. Did you know that in a study from South Korea’s Forest Research Institute, a 25-year-old cherry tree ca absorb about 20 pounds of emissions each year so this. beautiful tree also helps combat climate change in its ability to offset greenhouse gases. Another reason to love them, right?

The 10 Cherry Blossoms to Know and Love –

Mostly Yoshino cherry trees circle the Tidal Basin and spill north onto the Washington Monument grounds which most people know for their lush fluffy blossoms. Yoshino cherries produce many single white blossoms that create the effect of white clouds around the Tidal Basin. Known as Somei-yoshino in Japan, Yoshinos are a hybrid first introduced in Tokyo in 1872. Now, Yoshinos are one of the most popular cultivated flowering cherry trees.

Mingled with the Yoshino trees are a small number of Akebono cherry trees, a mutation of the Yoshino cherry with single, pale pink blossoms. Akebono trees were introduced by W. B. Clarke of California in 1920. The Akebono cherry trees flower at the same time as the Yoshino, providing a tint of pink in the early stages of the peak bloom.

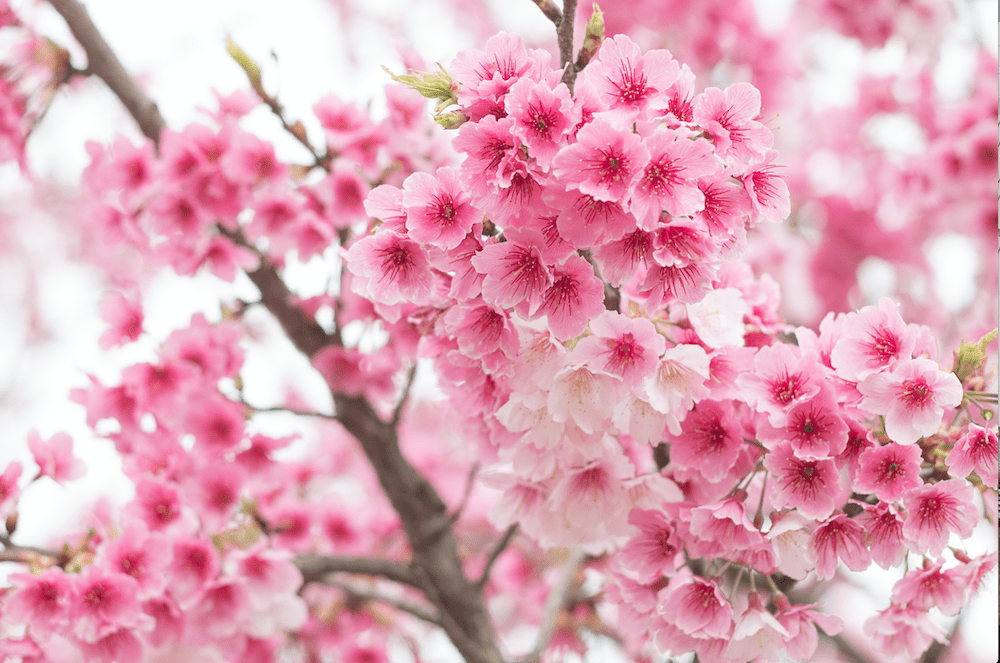

Kwanzan cherry trees are named after a mountain in Japan. Kwanzan cherry trees primarily grow in East Potomac Park. Coming into bloom two weeks later than the Yoshino, the upright Kwanzan branches produce heavy clusters of pink double blossoms.

In East Potomac Park, you’ll also find Fugenzo and Shirofugen trees. Fugenzo cherry trees blossom with double, rosy pink flowers. Shirofugen trees blossom with double flowers as well, white when the blossoms are open and aging to pink. Fugenzo cherry trees were originally planted along the Potomac River from the present site of the Lincoln Memorial south toward East Potomac Park, but gradually disappeared there.

The Weeping Japanese Cherry, sometimes called the Higan Cherry, is interspersed between the Yoshino, Akebono, and Kwanzan cherry trees. The flowers of the Weeping Cherry vary, blossoming as single or double flowers and in colors from dark pink to white. Weeping Japanese cherry trees flower about a week before the Yoshino trees.

Other tree types found in the park include the Autumn Flowering Cherry with semi-double, pink flowers, the Sargent Cherry with single, deep pink flowers, the Usuzumi Cherry with white-grey flowers, and the Takesimensis Cherry with clusters of white flowers.

Here are more details:

1)Yoshino Cherry (Prunus x yedoenis) – Approximately 70% of the total number of cherry trees in the park.

Habit: a round topped, wide spreading tree that reaches 30 to 50 feet at maturity.

Flowers: white, single in clusters of 2 to 5, and almond-scented.

History: This hybrid cherry of unknown Japanese origin was first noticed in Tokyo about 1872 and is now one of the favorite cultivated cherry trees of Japan. Zone: Hardy to USDA Hardiness Zone 6: Range of average minimum temperature 0 to -10 degrees Fahrenheit.

2)Kwanzan Cherry (Prunus serrulata “Kwanzan”) Approximately 13% of the cherry trees in the park.

Habit: an upright-spreading tree to 30 feet, with a rounded crown and stiff ascending branches. Wider than tall at maturity.

Flowers: double, with about 30 petals, in pendulous clusters of 3 to 5, sometimes more, clear pink and fading but small, up to 2½ inches across, with many more or less petaloid stamens often partly concealing the two green leafy carpels which protrude from the center of the flower.

Zone: Hardy to USDA Hardiness Zone 5: Range of average minimum temperature -10 to -20 degrees Fahrenheit.

3)Akebono Cherry (Prunus x yedoensis “Akebono”) Approximately 3% of the cherry trees in the park.

Habit: a round topped, wide spreading tree that can reach 30 to 50 feet at maturity.

Flowers: single, pale pink that fade to white, in clusters of 2 to 5.

History: This cultivar is losing popularity in the nursery trade and is being replaced with the cultivar Afterglow (Prunus x yedoensis “Afterglow”) which has pink blossoms that are deeper in color and do not fade.

Zone: Hardy to USDA Hardiness Zone 6: Range of average minimum temperature 0 to -10 degrees Fahrenheit.

4)Weeping Cherry (Prunus Subhirtella var. pendula) Approximately 2.4% of cherry trees in the park.

Habit: tree 20 to 40 feet high, with a round-flattened, gracefully, weeping crown. Usually grafted about 6 feet on the understock.

Flowers: single, pink. This variety is very variable and select cultivars differ in form and color. (i.e., “Pendula Rosea”, single deep pink flowers; “Pendula Plena Rosea”, double, pink flowers; “Pendula Alba”, single, white flowers; “Rosey Cloud”, double, bright pink flowers; “Snowfozam”, single, white flowers etc.). Zone: Hardy to USDA Hardiness Zone 5: Range of Average minimum temperature -10 to -20 degrees Fahrenheit.

5)Takesimensis Cherry (Prunus takesimensis) Approximately 5% of cherry trees in the park.

Habit: an upright spreading tree that can reach 30-40 ft. at maturity.

Flowers: white, in large clusters with short pedicels.

History: This species is known to grow in wet locations in its native habitat and is currently being tested in East Potomac Park for tolerance to excessive moisture.

Zone: Hardy to USDA Hardiness Zone 6: Range of Average minimum temperature 0 to -10 degrees Fahrenheit.

6)Autumn Flowering Cherry (Prunus subhirtella var. autumnalis) Approximately 3% of cherry trees in the park.

Habit: an upright rounded tree to 25-30 ft. with a 15-20 ft. spread.

Flowers: semi-double, pink. During warm periods in the fall and winter months they will open sporadically and then fully flower the following spring.

Zone: Hardy to USDA Hardiness Zone 4: Range of average minimum temperature -20 to -30 degrees Fahrenheit.

7)Usuzumi Cherry (Prunus spachiana f. ascendens) Approximately 1.3% of cherry trees in the park.

Habit: tree to 40 ft. with a round, gracefully ascending crown.

Flowers: single, white, truning to grey.

History: The trees in West Potomac Park are propagations from the 1,400+ year old Usuzumi tree growing in the village of Itasho Neo, in Gifu Prefecture of Japan. It is said that that the 26th Emporer Keitai of Japan planted this tree to celebrate his ascension to the throne. The Usuzumi tree was declared a National Treasure of Japan in 1922.

Zone: Hardy to USDA Hardiness Zone 6: Range of average minimum temperature 0 to -10 degrees Fahrenheit.

8)Sargent Cherry (Prunus sargentii) Less than 1% of cherry trees in the park.

Habit: Upright to 40-50 ft. with spreading branches approximately equal to height.

Flowers: single, deep pink, in clusters.

Zone: Hardy to USDA Hardiness Zone 4: Range of Average minimum temperature -20 to -30 degrees Fahrenheit.

9)Shirofugen Cherry (Prunus serulata “Shirofugen”) Less than 1% of cherry trees in the park.

Habit: a flat topped, wide spreading tree to 20-25 ft.

Flowers: double, in large clusters, white when open aging to pink.

Zone: Hardy to USDA Hardiness Zone 5: Range of Average minimum temperature -10 to -20 degrees Fahrenheit.

10) Okame Cherry (Prunus x “Okame”) Less than 1% of cherry trees in the park.

Habit: Upright tree to 25 ft. with a 20 ft. spread.

Flowers: semi-double, pink. The earliest flowering cherry.

Zone: USDA Hardiness Zone 5: Range of Average minimum temperature -10 to -20 degrees Fahrenheit. USDA Hardiness Zone 6: Range of Average minimum temperature 0 to -10 degrees Fahrenheit.

While Washington D.C. may have the most famous festival, there are now many others.

Macon, Georgia, calls itself the “Cherry Blossom Capital of the World.” Even though the trees are not a natural match for the area, it’s home to more than 350,000 Yoshino cherry blossom trees. Their International Cherry Blossom Festival is worth checking out too.

Out on the West Coast, Salem, Oregon had its Cherry Blossom Festival. Portland, Boston, Nashville and St. Louis each have a Cherry Blossom Festival. St. Louis with a mere 40 pale pink Yoshino trees still attracts appreciative crowds. Hawaii also has one.

The Cherry Blossom Festival in Washington, DC, began when the City of Tokyo, first in 1909, offered to donate 2,000 cherry trees to beautify the city. The president at the time, William Howard Taft, and his wife, Nellie, had lived in the Philippines and seen the cherry trees in Japan. The first shipment arrived in Seattle in 1910 and was transported to DC, where, when the trees were unloaded, it was discovered they were diseased. Yes, there was a Department of Agriculture back then, and they found nematodes and insects they did not want to infect American trees. President Taft gave the order and the 2,000 trees were immediately burned.

Burning of diseased cherry trees, courtesy of the U.S. National Arboretum

Burning of diseased cherry trees, courtesy of the U.S. National Arboretum

It did not cause an international incident, but it set the planting of the cherry trees back a bit. It was 1912 before another crop was gathered, and this time 3,020 cherry trees of 11 different varieties had been grafted onto a special root stock in Japan, then shipped to Washington and transported cross country, in insulated freight cars to Washington DC.

They were planted in 1912. A triumvirate of women – Nellie Taft, Iwa Chinda of Japan, and Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, the woman who had long campaigned for the new capital of the country to have its own grove of cherry trees – were there when the first two Yoshino cherry trees were ceremonially planted at the Tidal Basin, on March 27, 1912 in the presence of the Japanese Ambassador, to signal “friendship between the U.S. and Japan.”

These trees have been a symbol of friendship ever since – as well as beauty.

Jill Brooke is a former CNN correspondent, Post columnist and editor-in-chief of Avenue and Travel Savvy magazine. She is an author and the editorial director of FPD and floral editor for Aspire Design and Home magazine and contributor to Florists Review magazine.