Scientists Finding Way to Block Plant’s “Self-Fertilization”

By Jill Brooke

With food shortages and price hikes dominating the news, a new study in the journal Current Biology offers hope for better plant productivity.

As you may know, cereals, vegetables, fruits, and nuts depend on proper pollination since over 60% of our food comes from flowers. But what you may not know, is that many flowers and plants are hermaphrodites, having the male pollen located close to the female stigma. That means there is a constant risk of self-fertilization, which often results in unhealthy plants.

Now scientists through years of hard work and research have identified a new gene that combats self-fertilization. The research was done on Arabidopsis thaliana – a small weed related to crops such as cabbage and oilseed rape that is often used by plant scientists to better understand how plants function.

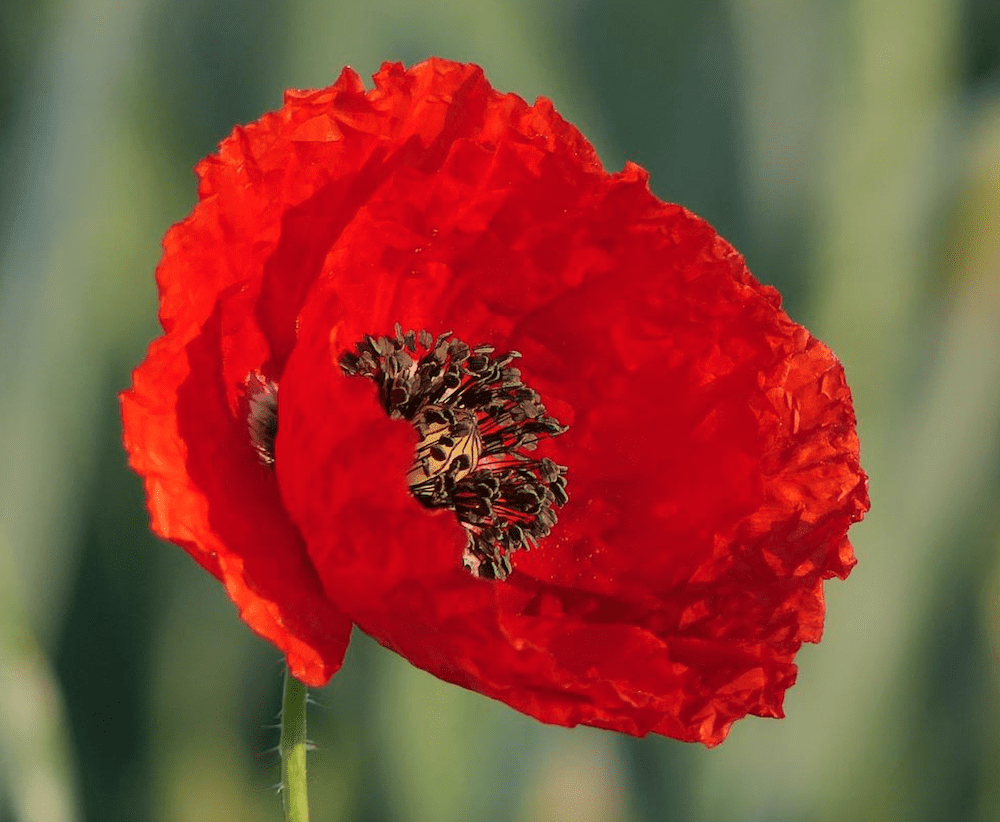

Lead scientist Vernonica Franklin-Tong also expanded research on her favorite flower – the poppy.

When asked if this was a way of preventing flowers from masturbation – in layman’s terms – Franklin-Tong, a professor of Plant Cell Biology at the University of Birmingham, quickly corrected me.

“Actually, it’s more a story about a story of sex and contraception… how plants prevent incest!,” she declared, prompting us to want to hear more about her research as well as the mysteries of plant and flower life.

“Plants use cell-cell conversations between the male and female tissues,” she adds. “With a self-incompatibility system (and ~50% of plants have this), plants use this system to recognize if the pollen is “self” (which is generally undesirable, as this leads to inbreeding and loss of fitness, with poorly plants) or not. So, it’s like a traffic light system, with “self” encounters resulting in a “stop” signal and “cross” pollination encounters having a “green light”. There are several different systems, but in poppy, they use a signal to tell the self pollen to commit suicide.”

Turns out the gene – named “Highlander” after the 1986 film with an immortal warrior – encodes a protein called PGAP1 which is found in all complex organisms, from yeast to humans. The genetically modified Arabidopsis plants showed no evidence of developmental defects, while its self-incompatibility was completely abolished and high levels of self-seed set were observed. Meaning for us humans – better yields and food production.

“This is a major breakthrough, as it not only identifies a new mechanism that is critical for achieving self-rejection of incompatible pollen, but it also implicates a role for specific proteins, called GPI-APs in this process for the first time,” says Franklin-Tong,

We wanted more details so Vernonica kindly clarified some questions.

1). Flowers produce up to 60% of food – why is this study important? With what is happening in Ukraine, food supplies are an issue – will this be helpful?

Well, we all know that pollination is important, and so many crops (fruit, vegetables, nuts, staple cereals, oils and pleasures like coffee and chocolate) are the end product of pollination. This study will not directly benefit us anytime soon, but maybe in the future. The idea is that if plant breeders get interested in this, using a self-incompatibility system may provide a cheaper and easier way to breed F1 hybrid plants.

2). What are you most excited and proud of with these results?

This was really a very fundamental scientific project, carried out by Zongcheng Lin, who was a Ph.D. student of mine ~10 years ago. He took part of the poppy self-incompatibility project (working at VIB in Ghent, Belgium) and uncovered this whole new area of these modified proteins called GPI-APs, that we weren’t expecting to find. That is really exciting to find something so unexpected! And it means the research will go in a whole new direction. Zongcheng is now just starting his own lab, back in China, and I’m so proud to be part of this story, as science depends on teamwork. And it’s the beginning, not the end of the story. Science is a bit like a detective story: you never know quite where it’s going to lead you; you just have to follow the clues and the evidence.

3) What prompted you to study this?

That’s a long story. We’ve been looking at various aspects of what controls and regulates self-incompatibility in the poppy system for a long time and have discovered several components that are involved. This project was to “screen” for further components, so at the time we had no idea what we’d find. We were hoping and thinking it would uncover something more about the cell suicide system (called programmed cell death), but finding “Highlander” was a huge surprise and had us wondering what was going on for a while.

4). What prompted you to study flowers?

I’ve always loved plants; I spend a lot of my spare time gardening and photographing flowers. It’s always a thrill seeing a new baby plant emerging from seed and watching it grow! What they do at a cellular level is also fascinating. It was pure serendipity that I ended up in the career that I did. I had just graduated in Botany (so was already showing an interest in plants) and had done unexpectedly well, and on graduation day I was asked whether I wanted to do a Ph.D.… on population genetics of self-incompatibility in poppies. I wasn’t sure I was up to it, but I jumped at the chance. I changed the direction of the research, as the population genetics was too theoretical for me, but I started playing with pollen in the lab and found a neat system to study self-incompatibility in a dish. It all went from there; the rest is history. I’ve spent 40 years playing with poppies and self-incompatibility now. My best friend is still amazed that I haven’t worked it all out yet! But it’s been a wonderful journey, learning lots along the way, and I still enjoy it.

Lucky us that Vernonica is so patient, dedicated, and devoted to plant and flower research and we will share more stories in the future.

Jill Brooke is a former CNN correspondent, Post columnist and editor-in-chief of Avenue and Travel Savvy magazine. She is an author and the editorial director of FPD, floral editor for Aspire Design and Home magazine and contributor to Florists Review magazine.