How Old Are Flowers? 99 Million Years or 250 Million Years

By Jill Brooke

How old are flowers? As we reported earlier, a report in New Scientist reveals that flowers may have existed over “250 million years ago, more than 100 million years earlier than the oldest fossilized flowers so far found.” But now a new study has found preserved flowers that are 99 million years old.

Those of us fascinated by the beauty and magic of flowers have believed a flower emerged 135 million years old, and then quickly diversified 130 million years ago.

Does this matter? Perhaps not. In fact, while Daniele Silvestro at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland, and his team made the announcement of the 250 milion-year-old flowers, after analyzing more than 15,000 fossils from around 200 different flowering families to create their timeline, it was cause for a surprise since it was so much older than originally thought.

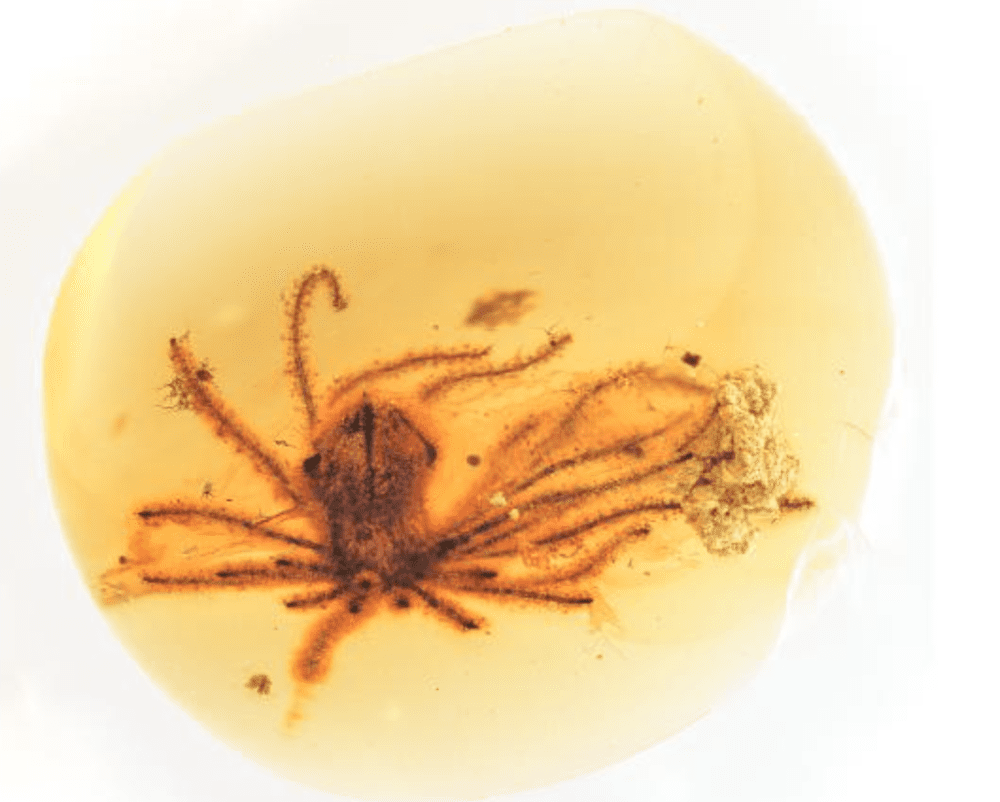

Now a new study from the journal, Nature Plants, found preserved flowers that are at least 99 million years old after scientists discovered some flowering plants in South Africa that are preserved in amber.

Here are deets of their study.

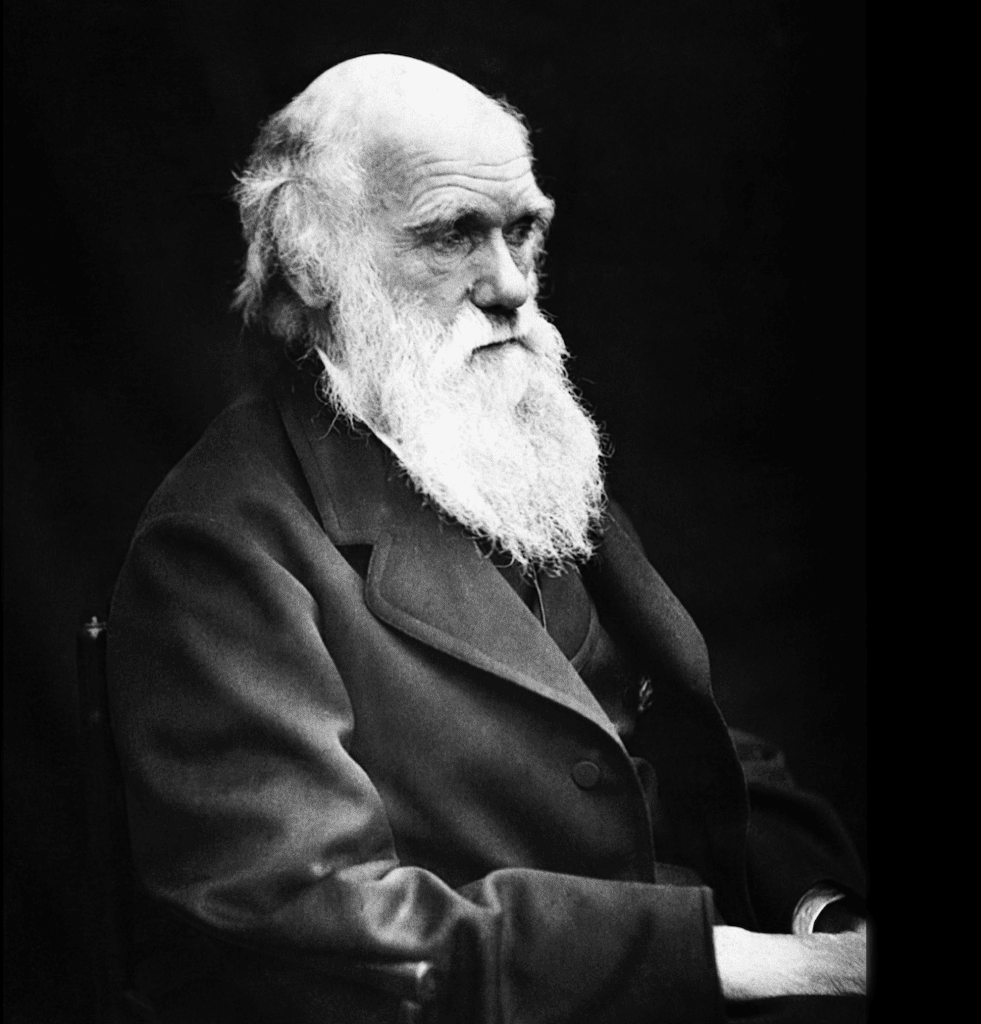

The two flowers once bloomed in what is now Myanmar may shed light on how flowering plants evolved — a major episode in the history of life that was once described by Charles Darwin as an “abominable mystery.”

Yes, flowers are ephemeral are hard to capture in their cycle of life. “They bloom, transform into a fruit and then disappear,” says writer Katie Hunt. “As such, ancient flowers aren’t well represented in the fossil record, making these ancient blooms –– and the history they carry with them — particularly precious.”

“Leaves are generally produced in larger numbers than flowers and are much more robust — they have a higher preservation potential. A leaf is discarded ‘as is’ at the end of its useful life, while a flower transforms into a fruit, which then gets eaten or disintegrates as part of the seed dispersal process,” said study author Robert Spicer, a professor emeritus in the School of Environment, Earth and Ecosystem Sciences at The Open University in the United Kingdom.

“These particular flowers are almost identical to their modern relatives. There really are no major differences,” added Spicer, who is also a visiting professor at Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden in China.

The evolution and spread of flowering plants (angiosperms) is thought to have played a key role in shaping much of life as we know it today. It brought about the diversification of insects, amphibians, mammals and birds and ultimately marking the first time when life on land became more diverse than in the sea, according to the study.

“Flowering plants reproduce more quickly than other plants, have more complex breeding mechanisms — a wide variety of flower forms, for example, often in close ‘collaboration’ with pollinators. This drives mutual coevolution of many lineages of plants and animals, shaping ecosystems,” Spicer said.

One of the flowers preserved in amber was named by researchers Eophylica priscatellata and the other Phylica piloburmensis, the same genus as the Phylica flowers that are native to South Africa today.

Mystery solved? Not really. More always to learn about flowers. Plus there are many flowers that become extinct which complicates things as well. But Darwin was always fascinated by flowers as a peek into evolution.

The sudden appearance of flowering plants in the fossil record in the Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago), with no obvious ancestral lineage from earlier geologic periods, had puzzled Darwin. It appeared to be in direct contradiction to an essential element of his theory of natural selection — that evolutionary changes take place slowly and over a long period of time.

It was in a private letter to botanist Joseph Hooker in 1879, published in a 1903 volume of Darwin’s letters, that he described it as an “abominable mystery.”

Exactly when flowering plants first emerged still isn’t clear, Spicer said, but the early flowers preserved in amber do shed some light on the mystery.

The specimens exhibit traits that are identical to those seen in flowers in fire-prone areas, such as the unique fynbos regions of South Africa. All 150 species of Phylica are native to this biologically rich and diverse region. They were also found alongside amber that contained partially burned plants.

“Here we have preserved in amber all the details of one such early flower just at the time when flowering plants begin to spread across the globe, and it shows superb adaptation to seasonally dry environments that support vegetation exposed to frequent wildfires,” Spicer said.

“If many of the early flowers were exposed to fires in such semi-arid landscapes, it explains why the early phases of angiosperm evolution are so poorly represented in the fossil record — fossil(s) do not normally form in such semi-dry environments,” he added.

Spicer said that fire must have been a frequent event over a long period of time for evolution to have shaped the flowers into a form that could cope with fire and produce seeds that can find their way into the burned land surface. In Phylica’s case, their flowers are protected by leaves that cluster at the twig tip.

While many ferns, conifers and some flowering plants seen today, such as plane trees and magnolia, grew during dinosaur times, Spicer said that Phylica piloburmensis was the first flowering plant known to have an all but identical relative alive today.

But that is debatable. Science by definition is about data and learning.

To unravel what the very first flower was like in the New Scientist study, a 36-strong team led by Hervé Sauquet of the University of Paris-South, France, spent six years analyzing the anatomical evidence of nearly every type of flowering plant to identify their most ancestral traits.

As James O’Donaghue wrote, studying the evolutionary roots is tricky because the delicacy of flowers means they rarely became fossilized. The oldest discovery was a 130-million-year-old aquatic plant Montsechia vidalii unearthed in Spain in 2015.

Either way, just shows you that our beloved flowers are at the core of human development in providing not only beauty but sustenance. As flowers evolved and adapted, they became food sources that allowed homo sapiens to evolve.

Jill Brooke is a former CNN correspondent, Post columnist and editor-in-chief of Avenue and Travel Savvy magazine. She is an author and the editorial director of FPD and floral editor for aspire design and home magazine and contributor to Florists Review magazine.