Christie’s Reveals How Women Empowered Botanical Art

Women have often been the unsung heroes of history rarely getting the credit they deserve.

As Christie’s revealed in a fascinating story, women also played a major role in the early days of plant science and botanical art though didn’t get the credit.

Until now.

A rare album of 18th-century drawings by Lady Maria Compton and her tutor Margaret Meen, is being sold this week at Christie’s. This sale sparked this research from the esteemed auction house which we are delighted to share with you.

By Jessica Lack

The 18th century was a golden age for botanical art.

Intrepid naturalists traveled to the far corners of the earth in search of parrot’s beak, ghost orchids and jade vine, certain that the analysis of such rare species would propel humanity from ignorance to enlightenment.

These scientists were often accompanied by virtuoso illustrators, who published their discoveries for the edification of the public. ‘Dare to know’ wrote the German philosopher Immanuel Kant in 1784, contending that the study of nature could provide mankind with the foundations for a better world.

While the names of male botanical artists such as Georg Ehret (1708-1770) and Pierre-Joseph Redoute (1759-1840) have lived on, the same cannot always be said of the women.

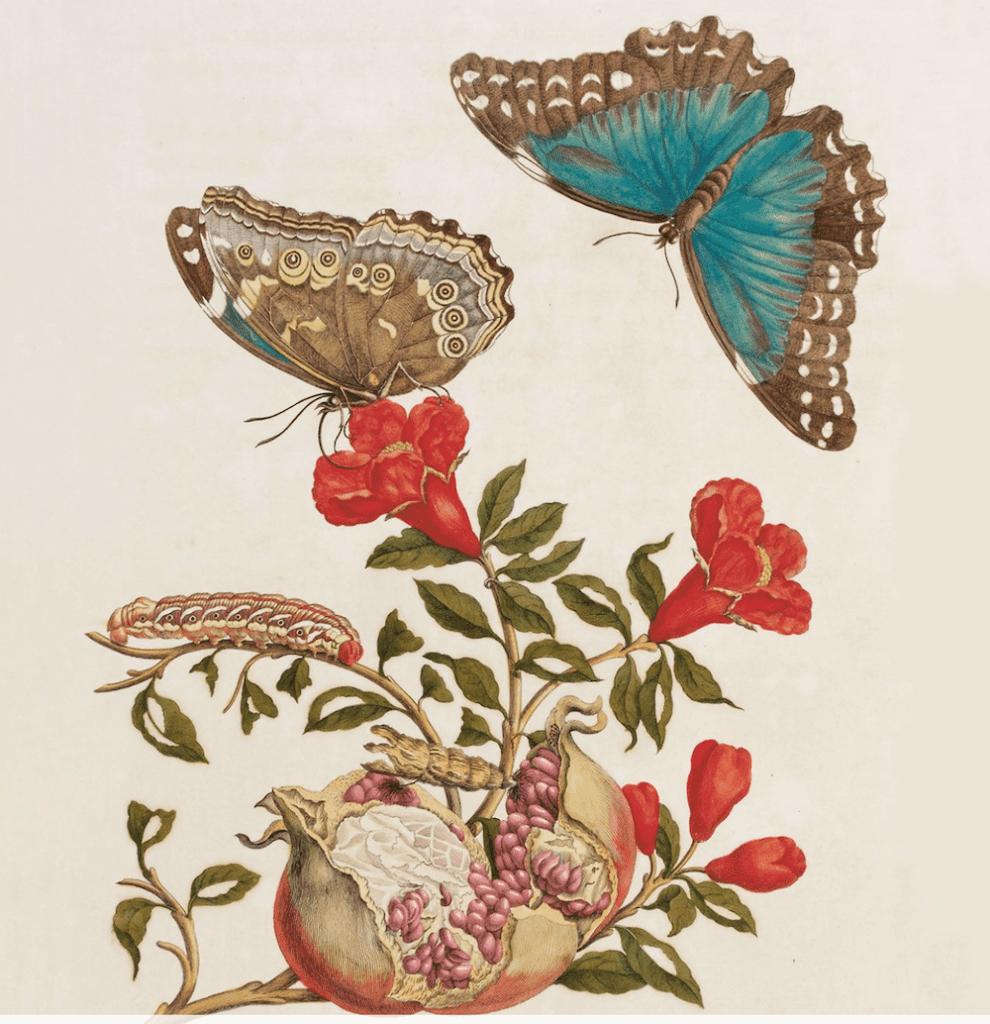

The Swiss entomologist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), who battled malaria in the Dutch colony of Suriname to record its flora and fauna, has only recently been recognized for her contribution to science. Likewise, Madeleine Basseporte (1701-1780), who served as the official painter of the King’s gardens in Paris, and had many of her paintings incorrectly attributed to Redouté.

Annabel Kishor, a specialist in British Drawings and Watercolours at Christie’s, explains that it was rare for 18th-century female illustrators to sign their paintings. ‘Quite often they only discreetly initialed their works,’ she says.

All of which explains why the discovery of an album of 69 botanical illustrations by Lady Maria Compton, Marchioness of Northampton (1766-1843), her teacher Margaret Meen (circa 1755-1824) and her niece Emma Smith (1801-1876) — who later married Jane Austen’s nephew — is such a rare find.

‘We know very little about these women, so this is a valuable record of three remarkably talented painters,’ says Kishor.

The album, which is offered online in the 300 Years of British Drawings sale until 8 December, has been in the Compton family for more than 200 years. ‘Maria’s son, Spencer Compton, became the president of the Royal Society, so I like to think she inspired a love of science and art in her children,’ says Kishor.

Lady Compton’s tutor, Margaret Meen, was one of the first artists to be employed by the Royal Botanic Gardens, established at Kew in West London in 1749 by Princess Augusta, the mother of George III.

‘It’s hugely significant that Kew Gardens was founded by a woman,’ says Kishor. ‘It meant it was a respectable place for women who were interested in art and science.’

Meen devoted her life to the study of plants, providing highly skilled scientific illustrations for publication. She also taught Queen Charlotte (the wife of George III) and her daughter Princess Elizabeth.

According to Kishor, the Queen was fascinated by botany, and spent many a happy hour illustrating the rare species brought back by the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820) from his voyage around the South Seas with Captain Cook.

Together with Banks, who became the unofficial director of Kew, she encouraged naturalists to crisscross the world in search of exotic finds, persuading sea captains to take great risks. Seeds and pressed flowers were sent back to Kew for research.

Thanks to this royal patronage, botanical illustration became a fashionable pastime for noble ladies. ‘Aristocratic women who normally wouldn’t be encouraged to discuss art and science were suddenly creating complex drawings based on the Linnaean system,’ explains Kishor.

The Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) established the binomial system of naming plant and animal species in 1735, and it is still used today. Working at Kew, Meen would have been very aware of such advances in science and incorporated them into her teachings.

A traditional 18th-century botanical illustration would have featured a single plant with a straight stem and the reproductive organs depicted to one side. However, Lady Compton’s flower paintings appear more animated.

Kishor suspects Meen’s students had more freedom than their male contemporaries. ‘These drawings were never intended for publication — that would have been considered vulgar. So Maria and Emma could be more experimental.’

The results are elegiac portraits of the natural world that anticipate the paintings of the Victorian botanist Marianne North (1830-1890), who travelled to the farthest corners of the globe to document flowers in their natural habitats. Her paintings are now housed in a special gallery at Kew.

‘You cannot know a plant just by its structure. You need to understand its nature and habits, see it move and experience its fragility,’ says Kishor. ‘Lady Compton’s paintings do just that. She understood that every flower is a unique individual.’

Images and story courtesy of Christies