How Flowers Are Used as Symbols to Stop Gun Violence

By Linda Lee

Putting a flower in a gun barrel is a bizarre act. You turn the gun into a vase.

On first glance, it seems pointless. You can’t disarm a rifle with a flower. But you can disarm a population with a photograph.

A 1967 photograph marks the first time a flower was used symbolically to stop violence. Up until then, flowers were placed on graves and showered on victors. They were handed out as bouquets.

Picasso did a watercolor called “Bouquet of Peace” in 1958 to commemorate a peace congress in Stockholm, Sweden. The peace implied might be a bit disingenuous, since the meeting was of the World Peace Congress, which condemned only “warmongering” by the United States (and not Russia’s invasion of Hungary two years previous) and was understood to be a Communist front. So let’s skip Picasso’s bouquet, which probably hung on dorm room walls during the 1960s, and is taught today in nursery schools as an excellent way to encourage children to try their hands in art. I don’t think it stopped any violence.

Instead, let’s look at two iconic photos of a march in October 1967: The impetus was the San Francisco instruction to confront soldiers and guns with toys, flowers and song. That was conveyed to New York organizers like Abbie Hoffman, who tried to inspire somewhat wary New Yorkers that they could toss around flowers and slogans like “Love one another” and “Peace, brother” and things would get better. After a few failed attempts, he and Jerry Rubin announced an October March on Washington and urged marchers to arm themselves with flowers. Because of underground newspapers, enough people got the message to grab daisies and carnations on their way to Washington.

Marchers did not look like stereotypical hippies, no more than most of the people a few years later at Woodstock. Some were high school students, like 17-year-old Jan Rose Kasmir, caught by the French photographer Marc Riboud confronting National Guardsmen armed with bayonets with her little daisy.

The same day a photographer from the Washington Star, Bernie Boston, took a photograph he titled “Flower Power” (image at top of page). It was of 18-year-old George Harris, wearing a turtleneck, holding a bunch of flowers in his left hand, and putting one into the barrel of the National Guardsman’s rifle. Would the zeitgeist be the same if these two photos had not been taken that day? But Boston and Riboud took their photos, and suddenly America, and news magazines, had images and a name for it. Flower Power.

It was when the woozie Flower Power juice from San Francisco joined the wild New York energy of Hoffman and Rubin that a new image of the antiwar movement was born. After that, posters showing guns in combination with flowers seemed to be everywhere.

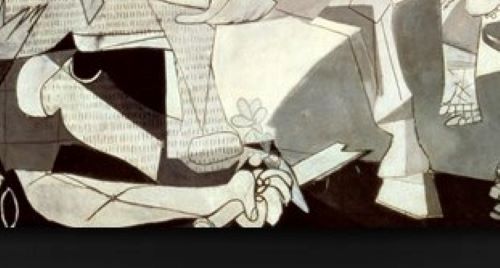

Pitting flowers against war is not a new idea. Picasso showed a flower being trampled by horses’ hooves (or sprouting from a broken sword) in “Guernica,” which expressed shock and horror at Germans bombing the Basque parliament building and town in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War. The painting is considered the most powerful piece of anti-war art ever created. Picasso refused to have it in Spain as long as the Fascist dictator Francisco Franco was in power. So it hung for decades at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, another form of protest that lasted until after Picasso’s, and then Franco’s, deaths. But this was not a flower fighting violence. It was a flower being overwhelmed by war.

By the way, the flower needn’t be representational. Consider one of Alexander Calder’s spider-like sculptures. Calder is not known for making his work “mean” anything, but the title of this 1945 work makes it unmistakable: “Bayonets Menacing a Flower.” Again, the flower would appear to be the loser, not the defiant winner, as evident in Raboud’s photograph. Bayonets did not win the day in 1967.

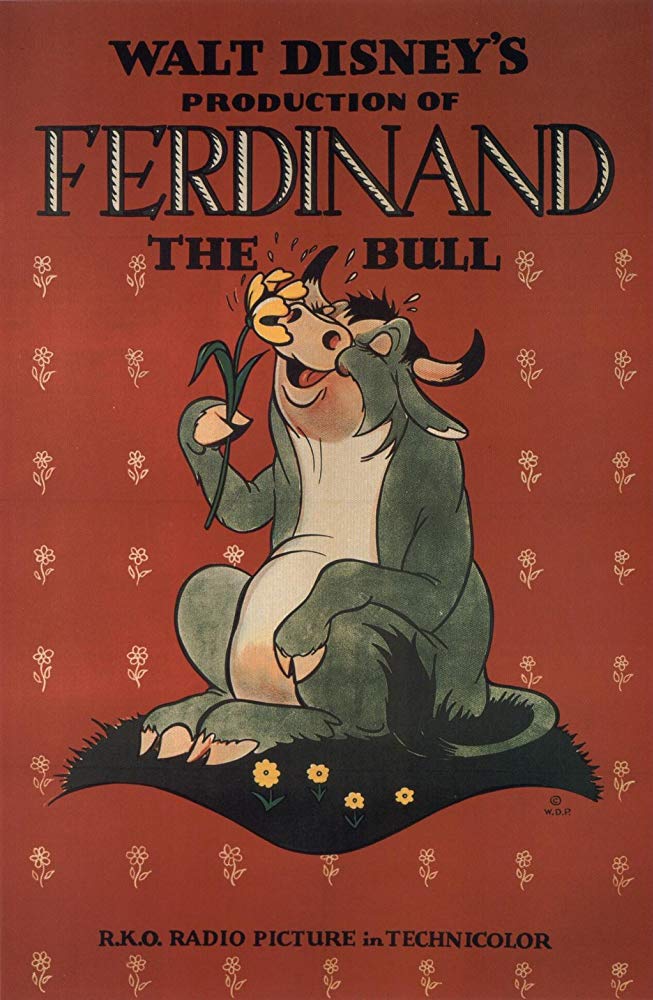

It’s interesting that the children’s story of “Ferdinand the Bull” was written just a year before “Guernica” was painted, contrasting a love of flowers with the need to fight. Many people believe Picasso was influenced by the story of Ferdinand, but Picasso did not need any help in deriving symbolism for Basque country. The Disney movie came out in 1938, at a time when the United States was doing its best to ignore the Nazi threat in Europe.

But again, the flowers that Ferdinand preferred did not defeat the much more warlike bulls. Ferdinand was just allowed to go his more peaceful way.

It was when someone put a flower into a gun barrel that the symbolic power of a flower was felt. Since then we’ve seen tank turrets wreathed in flowers, and flowers stuffed into every conceivable kind of weapon.

While it will not change the laws – only Congress can do that – it remains a powerful symbol: the fragility of a flower against the cold menace of a weapon.